Citizen Potawatomi Nation is Pottawatomie County’s largest employer with an economic impact of more than $500 million and has come a long way from the days when tribal services were conducted by volunteers and run out of the old trailer.

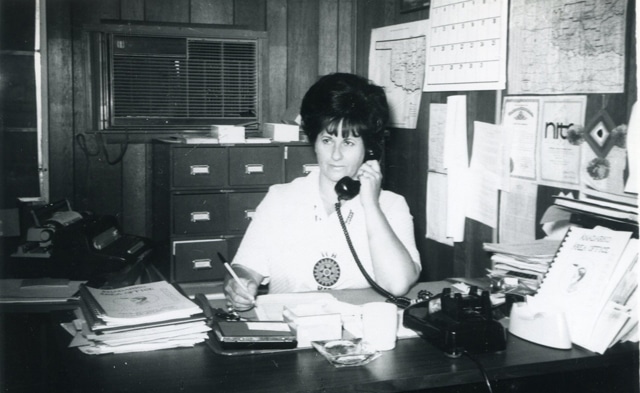

Amongst many others who worked for the tribe before and after the landmark 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, tribal elder Beverly Hughes witnessed the changes first hand. Elected Secretary Treasurer in 1970, she served on the five person Business Council, then the tribe’s governing body.

Her primary work was serving the tribe to get contact information for members in order to get out the per capita payment from the government. To accomplish this, Hughes secured a $25,000 federal grant to fund the outreach effort. The result of this was the publishing of the very first edition of the Hownikan, which was printed on a Community Health Representative Xerox machine.

“All I was trying to do was give people an update on what we were doing and what services we provided,” explained Hughes. “It seemed pretty popular, so from then on we tried to produce it every quarter to keep our members informed.”

The 1970s were a time of increased independence for Native American tribes across the country. For the first time in centuries, the rights of self-governance were given to the tribes themselves, albeit with oversight still in the hands of the Bureau of Indian affairs. Tribes, who had always been sovereign entities, finally had the independence to act in the interests of their members. These changes also saw the establishment of cultural aspects that had been neglected under BIA oversight. For the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, the duty of codifying the tribe’s proper spelling and designing a tribal seal fell to Secretary -Treasurer Hughes.

“We had an intertribal meeting for the tribes in the Shawnee area (Iowa, Sac & Fox, Absentee Shawnee, Kickapoo and Citizen Potawatomi), and our chairman at the time needed a tribal seal and flag for the meeting. So we talked about it, I went out and bought some materials and came up with the first seal we’d ever had,” said Hughes.

In a later meeting, a BIA staffer explained the need to get a consistent spelling of the tribe’s name. For years confusion had reigned over the multiple spellings, the two most popular of which were Potawatomi and Pottawatomie.

“They said they were going to spell it the same as the county,” recalled Hughes, “but I told them that we were separate from the county. We were an entity unto ourselves, so we made it Potawatomi.”

Hughes eventually left the Business Council, and retired from Tinker Air Force base after nearly twenty years of service there. Looking back over her time working for the tribe, some of it spent as a volunteer, the Bruno-Rhodd-Bourbonais descendant is excited for the future of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

“I know going way back, Chairman Barrett wanted every member to have the benefits and services we provide wherever they lived. With as many members that we have, that isn’t always possible now. But is his goal to accomplish that before he leaves office. We aren’t the richest tribe, but we will get there. And when we do, we will be able to help everyone regardless of where they are,” said Hughes.

Though retired, she still attends tribal functions and is a mainstay at the CPN Eagle Aviary, which is managed by her two granddaughters Jennifer Randell and Bree Dunham. As the person responsible for the paying out of the tribe’s last per capita payment in 1981, she explained why she thought the ending of payments and moving toward the tribe’s current strategy of reinvesting money into health care, commercial enterprises, education and social services was a good idea.

“Our old payments were repayments for land taken from our ancestors in the Great Lakes region,” explained Hughes.

In the 1970s, the tribe hired lawyers who assessed the value of those lands at the time of their transfer from the Potawatomi to the U.S. government. The subsequent settlement on behalf of the federal government in the 1970s as compensation was paid out to surviving Potawatomi tribal members. Hughes oversaw the final distribution of that sum, and pointed out the interest on that total is now used to fund the Health Aids Foundation and tribal scholarships.

“A few years ago I ran into a tribal member who asked me when we were getting our next payment. He’d just had heart surgery, and in his hand was a bag of prescriptions from our tribal pharmacy. I asked him how much he thought his surgery and medicine would have cost if he’d had to pay for it himself. He looked at me astonished and admitted, ‘Beverly, I hadn’t even thought about that. I am so grateful for the tribe because I’d never have been able to pay for this’. I looked at him and said ‘That is why it’s better to reinvest it’.”