Imagine you’re providing a service to a customer for an agreed upon price. You’re nearly finished with the project and the money stops coming in. The customer acknowledges that he owes you the money and in good faith you continue to provide the service. However, upon completion of the project the customer explains that he doesn’t have the money to pay you at the current time. This doesn’t sound like a good deal, does it? This hypothetical situation hasn’t just taken place in real life; it has been how things are done between Native American tribes and the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Services for decades.

The Indian Self Determination Act of 1975 authorized government agencies to make grants directly to federally recognized tribes so that those tribes would have authority for how they administered those funds. The act has allowed tribes to have greater control over their welfare and also has enabled tribes to provide programs and services to the greatly underserved Native American population.

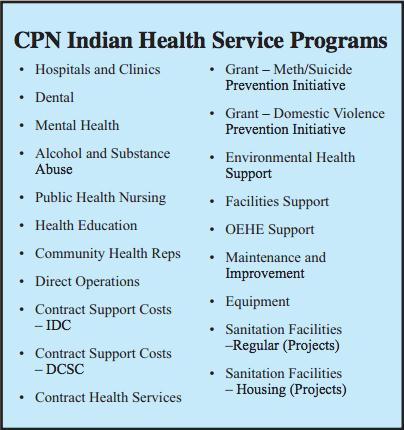

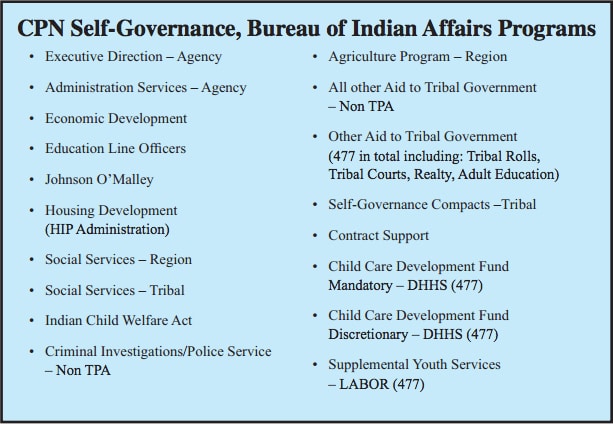

The largest of these programs and services fall under two categories; Indian Health Services (IHS) and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Every self-determination contract with these two agencies has a price attached to it for the work that tribes undertake on behalf of the federal government. Across the nation, tribes have taken over critical federal responsibilities in health care, education, law enforcement and land and natural resources protection.

According to testimony given by Native American law expert Lloyd B. Miller to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Oversight Hearing, not a single tribe in the United States is without at least one self-determination contract with either IHS or the BIA. Annually tribes administer some $2.8 billion in essential federal functions, employing an estimated 35,000 people.

For decades, there has been growing concern regarding the underpayment of contract support costs from these federal agencies. Underpayment of these contracts resulted in reduced services and the creation of contract support cost funding provisions. According to Miller, IHS underfunded tribes by nearly $100 million per year, while the Bureau of Indian Affairs also failed to meet contract obligations.

A series of lawsuits and two United States Supreme Court decisions ruled in favor of tribes. The Court ordered IHS and the BIA to pay tribes the millions on contract support costs that they deserved. However, these court actions have not resulted in payment, but rather have resulted in these Federal Agencies looking to further escape liability.

After more than a decade, the United States Supreme Court rejected the Agencies’ new methods and ruled in favor of the tribes again. Progress remains slow for tribes looking to collect on the funds owed to them. The Citizen Potawatomi Nation began submitting claims for contract support costs in 1997 and is owed an estimated $16 million. It is estimated that 229 tribes are owed about $350 million.

Now, more than a year after the second U.S. Supreme Court ruling, only a few court cases have been settled, many for much less than the tribes are contractually owed. IHS has taken the position that damages should be calculated on what the tribes spent, rather than what they were contacted.

In addition to the lack of funds and reduced programs and services, underpayment puts working relationships between the U.S. Government and tribes at risk. Rather than be an advocate for Indian Country, IHS and the BIA have tried to cut funding and change the agreed upon system of payment. The reality is that they have been advocating for the United States government and not those they are designated to protect.

The litigation process is wasting valuable resources that could be used for programs and services across the country. We need to get back to the business of taking care of people.

The Indian Self Determination Act has been a success, despite these roadblocks. It has allowed tribes to take control of the welfare of its citizens, provide jobs, and serve hundreds of thousands of people across the United States. Our own CPN health and wellness programs provided more than 62,000 physician visits, dental appointments and wellness visits in 2012. These programs also allow us to manage our land, provide scholarships and continue to grow our tribe.

It’s time for Congress to force federal agencies to pay the fair contract costs to tribes for the services that tribes are providing so that valuable time and money can be refocused on helping the most underserved portion of United States residents.