As the Vietnam War entered its second decade, American policy makers made another attempt at severing the Communists’ Ho Chi Minh Trail, which crept along the porous borders of Laos and Vietnam. Tribal member Robert Sander, a helicopter pilot with the 101st Airborne, took part in the operation. More than twenty years after the operation, which failed to halt the line of supplies to the Communist forces, a session of light reading about the doomed operation piqued an interest into the various political, military and geostrategic decisions made which sent him and his fellow soldiers into battle.

As the Vietnam War entered its second decade, American policy makers made another attempt at severing the Communists’ Ho Chi Minh Trail, which crept along the porous borders of Laos and Vietnam. Tribal member Robert Sander, a helicopter pilot with the 101st Airborne, took part in the operation. More than twenty years after the operation, which failed to halt the line of supplies to the Communist forces, a session of light reading about the doomed operation piqued an interest into the various political, military and geostrategic decisions made which sent him and his fellow soldiers into battle.

Now, with Operation Lam Son 719 more than 40 years behind him, the former chopper pilot has published an in-depth examination of the 1971 military operation. The Navarre-family descendent sat down with the Hownikan to discuss his experiences in uniform, the motivation in digging up such personally painful memories and the positives to finishing his book.

Tell us a bit about yourself in terms of where you came from, and how you ended up connected to the operation that forms the central theme of your book.

“I grew up on a farm west of Seiling, Oklahoma. I graduated from Seiling High School in 1964 and continued my education at Oklahoma State University. During my first two years at OSU all male students were required to attend Reserve Officer Training Corps classes, which I continued during my junior and senior years. Upon graduation in 1968, I was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and attended the Artillery Officers Basic Course at Fort Sill, Okla. followed by Ranger training at Fort Benning, Ga. In 1969 I volunteered for flight training and duty in Vietnam. After flight school I received orders to attend the Aviation Maintenance Officers Course at Fort Eustis, Va. followed by the AH-1G, Cobra Gunship training course at Savannah, Ga. I was promoted to captain in 1970 and arrived in Vietnam in early 1971. I was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division.”

What was it like serving as a Native American during that time?

“While I was aware of my Native American heritage, I really never gave it much thought and doubt that those who knew me were aware of my heritage. Occasionally, in social settings, someone would ask if I was if I was ‘Indian’ or Hispanic. When I replied ‘Potawatomi’, some thought I was pulling their leg, and that Potawatomi was just a made-up name. For the majority of my time in Vietnam I was assigned to D Company, 158th Assault Helicopter Battalion, whose call sign, ironically, was ‘Redskin.’

As a result, while some are offended by this term, I wear it with pride.”

You’ve explained that completing this work was a labor love. Why go to such an effort?

“The topic is one that digs deep into my emotions. I never wrote the book with a view toward personal profit or recognition. It is not an autobiography. My name appears only on the cover. I guess that more than anything it is a tribute to my ‘band of brothers.’

Some of the fallout of Lam Son 719 was a brief but intense squabble between the Army and Air Force as well as efforts by the major players in the policy decision to fix blame on anyone but themselves. It is not necessarily a part of our history that generates pride in our national leadership.”

As you look back over your years of research and writing, what are some insights you’ve uncovered about the book’s main topic?

“Operation Lam Son 719 was an attempt to sever the North Vietnamese supply and infiltration routes in Laos known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. While a lot of people like to believe that the U.S. won all the battles during the Vietnam War, which is not the case. Lam Son 719 is but one example.

In late 1970, Congress attached an amendment to the defense appropriations bill that prohibited American ground troops from crossing the borders of Laos and Cambodia. Yet there was a legal loophole that excluded air support and the attempt to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail went forward with South Vietnamese ground forces supported by U.S. airpower. It was the largest airmobile operation in the history of warfare and the armada of Army helicopters supporting the South Vietnamese flew into an unprecedented antiaircraft environment that grew in intensity and lethality for 42 days. It was a defining event that shaped the lives of the pilots and aircrews involved, whose memories of friends lost have never faded.”

How did you come to the decision to undertake such a time consuming effort?

How did you come to the decision to undertake such a time consuming effort?

“After I retired in 1993 in began to do a little light reading to see if I could find out more about the operation. It was painfully obvious to Army aviators that the South Vietnamese army was not up to the task and that American lives were wasted in an impossible situation. I found that Lam Son 719 was rarely mentioned in literature and that most of what was written was incorrect, misleading or failed to satisfy my personal need to know the origins of the operation. Specifically I wanted to know why it failed and who was responsible.

Light reading evolved into research. Obviously the answers, if there were any, had to be found in government documents. I read volume after volume of government documents found in the U.S. State Department’s historical series, ‘Foreign Relations of the United States’, the memoirs of the major players in policy decisions, all pertinent military documents from the National Archives, gleaned the historical offices of the military services and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the US Senate, and the Central Intelligence Agency, and interviewed other veterans.

The decision to write the book was inspired by the CPN’s support for veterans and was confirmed in 2010 when I attended the services for two of my friends whose remains had recently been recovered and brought home. The book is by no means an individual effort. It is the result of a collaborative effort on the part of Mike Sloniker, who is the historian for the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association, Dr. Charles Rankin, Editor of the University of Oklahoma Press, and distinguished historians who assisted me in locating important documents and reviewed my manuscript. It is my hope that this book will bring a greater sense of closure for Vietnam veterans and their families and a greater understanding of a small slice of our national history.”

You’ve obviously dug up some painful memories, but have you experienced any closure or sense of reward as a consequence of your work?

“One of the most rewarding experiences I had while writing this book occurred when the University of Oklahoma sent the manuscript out for review. In it, I noted that I had difficulty in accepting the official cause of death for some of the casualties. Some were written off as an ‘accident’ when in my opinion, the death was directly attributable to the combat environment – and I cited an example.

As it turned out, one of the pilots killed in this ‘accident’ was a family member of a U.S. Air Force civilian historian selected to review the manuscript. Some of details of his death were never disclosed to the family. That historian and I have since become close friends and she was of immeasurable assistance in assisting me to dig up some important documents that I would have otherwise never found. I would like to think I brought a little closure to that family.”

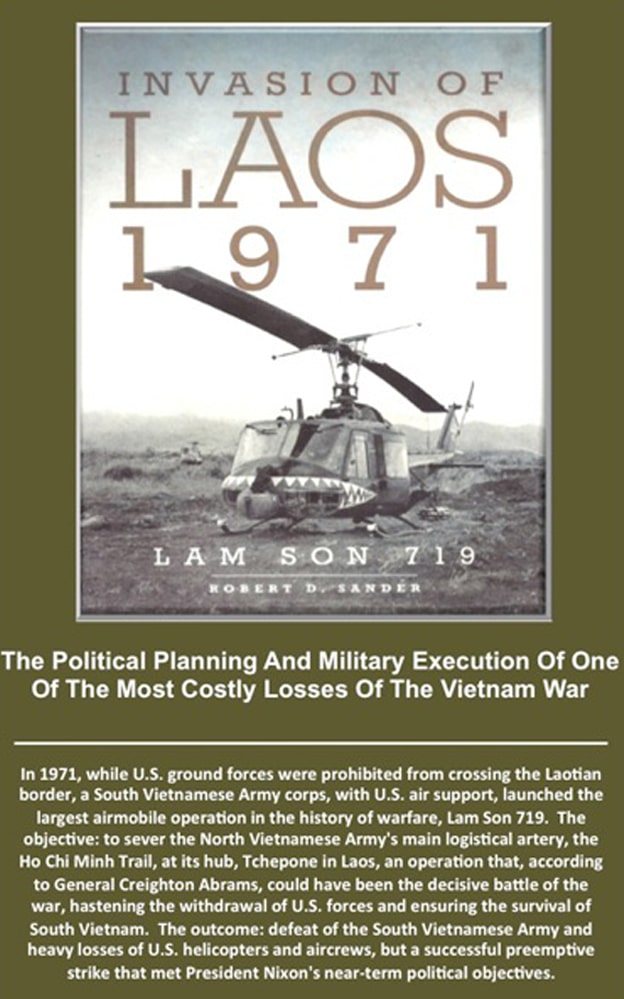

Robert Sander currently lives in Oklahoma City and is easing into retirement and his role as a grandfather and amateur historian. His book, “Invasion of Laos 1971” is available on Amazon.com and from the University of Oklahoma Press at www.oupress.com.