Editors Note: On Sept. 20, 2021, the City of Shawnee formally de-annexed the land south of the North Canadian River. The detachment ended the legal dispute between the City of Shawnee and Citizen Potawatomi Nation. On Sept. 21, 2021, Leaders from the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and City of Shawnee announced Tuesday the launch of Shawnee Aligned, a new initiative wherein the two governments will seek opportunities to collaborate for the betterment of the Shawnee community. Read more here.

Here are the facts about the City of Shawnee’s actions towards the lands held in trust by the United States Federal Government belonging to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

Article 1, Section 8 of the United States Constitution vests Congress the authority to engage in relations with Native American tribal governments. Challenges to this principle began in earnest in the 1830s as U. S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall articulated the fundamental principle that has guided the evolution of federal Indian law; that tribes possess a nationhood status and retain inherent powers of self-government.

The City of Shawnee has no more a right to dictate to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation than the Republic of France.

In 1867, ancestors of today’s Citizen Potawatomi Nation purchased land from the government of the United States in what was then Indian Territory. Today these lands are primarily in Pottawatomie County. These Tribal lands were overseen by the U.S. federal government on behalf of tribes and their members. They were and remain governed by federal law.

On December 12, 1961, the Shawnee City Commission rushed an emergency hearing to vote on annexation of lands around the Pottawatomie County Hospital. Though all such meetings require 48 hours public notice, the 1961 commission’s actions gave only 19 hours’ notice. According to the meeting minutes, they made no attempt to post public notice. Records also show commissioners made no effort to determine the rightful owners of the land and ask permission for the annexation, a binding legal requirement under state law.

The 1961 Oklahoma statutes on land annexation required land be annexed by petition, requested by land owners or with written consent from three quarters of the land owners. They further stipulate that legal notice of the annexation must be published in local newspapers at least once for two successive weeks ahead of any meeting. The 1961 Shawnee City Commission had no written consent from either the Citizen Potawatomi Nation or the federal government, the two land owning parties. The only legal notice published about the annexation ran in the newspaper two days after the vote took place. Despite these violations, CPN lands were illegally annexed by City Ordinance 156NS.

When the tribe questioned the validity of this action in 2014, then-City Manager Brian McDougal claimed in interviews with the Countywide and Sun and Journal Record that the city’s records indicate a legal annexation. To date, despite freedom of information requests, the city has refused to produce public records verifying McDougal’s claim.{jb_quote}To date, despite freedom of information requests, the city has refused to produce public records verifying McDougal’s claim.{/jb_quote}

For decades the portions of tribal land illegally annexed laid largely unused as the City of Shawnee grew towards the Interstate 40 corridor. Town leaders made little effort to improve infrastructure or promote commercial investment in these properties where many Potawatomi and Absentee Shawnee tribal members resided.

Following the passage of the 1975 Indian Self-Determination Act, tribes like CPN began to gain a hold on their own affairs, especially in terms of economic development and business investment. Through management of federal funds and revenue from tribal enterprises, CPN slowly built up the infrastructure in these areas long-forgotten by city hall. Today the tribe is the county’s largest job creator with 2,200 employees. In fact, 70 percent of the new jobs created in Shawnee for the past decade have been CPN hires.

This development and success finally drew attention of Shawnee’s leaders. In 2012, following an agreement with the Shawnee City Commission, CPN provided $625,000 for the resurfacing of the southbound lanes of the James W. Allen bridge, which crosses the North Canadian River and begins Gordon Cooper Drive. The tribe also donated $100,000 to the city’s municipal pool project, again, at no cost to Shawnee’s city leaders. This generosity and commitment to improving the community is the standard for CPN. Nearly 200 civic and community organizations have been the benefactors of CPN’s generosity for a total of more than $5 million since 2005. Additionally, CPN has contributed more than $34 million toward public facilities and nearly $40 million for water and sewer infrastructure, roads and public safety in the past decade.

{jb_quoteleft}In 2012, following an agreement with the Shawnee City Commission, CPN provided $625,000 for the resurfacing of the southbound lanes of the James W. Allen bridge, which crosses the North Canadian River and begins Gordon Cooper Drive.{/jb_quoteleft}While this cooperation proved fruitful for both, the city’s fathers instead saw tribal economic success as cash cow to be exploited.

Just days after the tribe’s municipal pool donation, a letter from Mayor Wes Mainord was released to The Shawnee-News Star prior to being served by armed Shawnee municipal police officers to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. The letter, dated Feb. 4, 2014, claimed that city sales tax revenues were down due to tribal enterprises like FireLake Discount Foods. Like many city claims, these assertions proved hollow. Independent audits of its finances show that tax revenue has increased each year since 1996, with the exception of the fiscal year 2009-10.

Though the tribe disputed the city’s claims, in an effort to preempt litigation, CPN hosted a meeting to discuss the matter at its tribal museum and heritage center on March 24, 2014. The meeting’s tone was not one of mutual respect, but rather was marked by an increasingly condescending rhetoric from the city’s delegation. At one point, as tribal leaders explained their governments’ sovereign status, Mayor Mainord questioned the loyalty of tribes to the United States, asking if they recited the pledge of allegiance.

On March 31, the city’s public utility crews flushed an unmapped water line that ran beneath the CPN Cultural Heritage Center. This resulted in extensive structural damage in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, with reconstruction efforts still ongoing as complications continue to arise from the original flood. On April 7, 2014, City Manager Brian McDougal admitted to the city commission that it had been a city water line that had caused the flood.{jb_quoteright}At one point, as tribal leaders explained their governments’ sovereign status, Mayor Mainord questioned the loyalty of tribes to the United States, asking if they recited the pledge of allegiance.{/jb_quoteright}

In June, CPN supported candidates for the town’s city commission elections who told voters they would vote to defund the city’s law firm who was pursuing litigation against the tribe. At this time, though it disputed the original 1961 annexation, the tribe began exploring the feasibility of officially detaching only its tribal lands from the town. Following the election of two candidates the tribe had supported, lame duck commission members along with Mayor Mainord, Vice-Mayor James Harrod and Commissioner Keith Hall pushed through an amendment to the city charter concerning detachment petitions that had been unchanged since 1908.

At the Sept. 15, 2014 city commission meeting, Commissioner Hall requested a vote that would allow investigations of city commissioners who may have a conflict of interest with the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. When questioned by Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman John Barrett about his motive for the investigation, Hall responded that his issue was not with the members of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, but rather with its leadership.

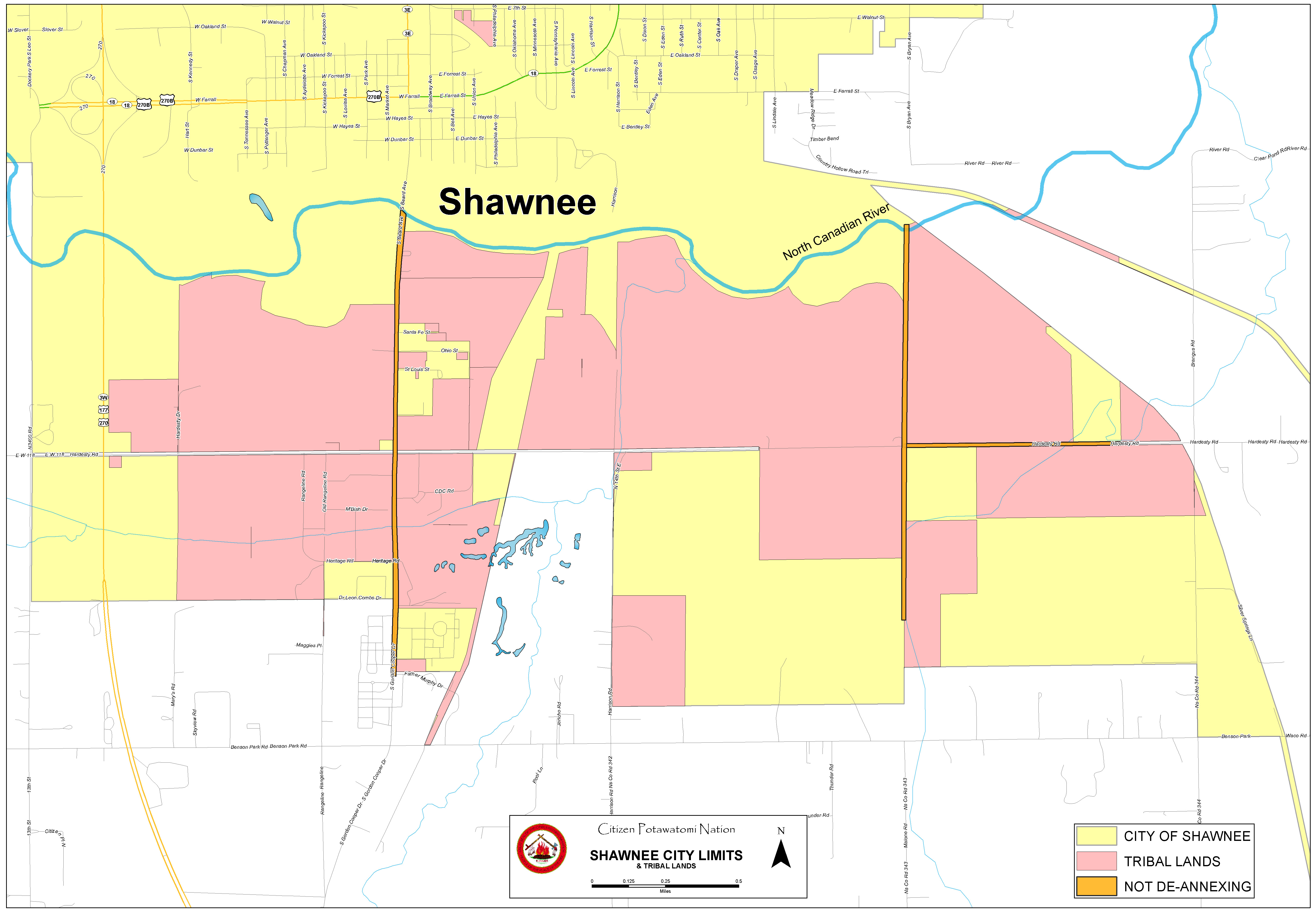

On Sept. 10, Citizen Potawatomi Nation filed a detachment petition with the City of Shawnee for tribal land held in trust by the federal government. Shawnee City Clerk Phyllis Loftis denied the petition on the grounds that CPN was not the legal owner of the property because of its status as federal trust land.

In response, Asst. Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin K. Washburn wrote a letter to Citizen Potawatomi Nation affirming that “Indian tribes are the beneficial owners of land held for them in trust by the United States. As such, tribes enjoy full and exclusive possession, use and enjoyment of tribal lands. Further, tribal governments exercise jurisdiction over trust lands and trusts lands are generally exempt from jurisdiction of local and state governments, except where Congress has specifically authorized jurisdiction.”

In protest of the decision by Loftis, CPN filed a civil complaint in Pottawatomie County District Court requesting action on the petition detachment by the city commission. On Dec. 19, 2014 a judge ruled that city commission must grant Citizen Potawatomi Nation a public hearing on its detachment request.

The past year’s tension has done little for either the city or the tribe. Citizen Potawatomi Nation has attempted to play by the town’s rules in order to resolve the situation. At every turn the tribe’s efforts have been met with hostility. When it supported candidates in the local elections, their integrity was publicly questioned by fellow commissioners. Upon requesting a fair public hearing for detachment of its lands, the city denied the fact that CPN even had the right to do so. As it became clear to CPN nearly one year ago, the tribe and its interests can not receive a fair hearing on any matter from certain elements of Shawnee’s city government. In requesting formal detachment of what is legally its own land, Citizen Potawatomi Nation seeks to put an end to this senseless bickering. Many of our members and employees live, work and shop in Shawnee. This will not change even if city leaders get the Pyric Victory they evidently seek. It is time to move on and forward, separately, for our shared communities.