The resurgence in positive portrayals of Native American culture has come with unforeseen consequences in recent decades. A drive for purity – specifically in terms of defining what it means to be Indian – has become a prominent topic of discussion in places like Oklahoma, where so many tribal nations, cultures and peoples intermingled.

Thanks in part to a rise in the appropriation of headdresses, a ceremonial symbol for warriors and leaders typically associated with tribes from the Great Plains region, it seems that the country is only one concert or poorly managed publicity stunt away from debating the famous Native American head adornment. Yet a deeper question emerges in places like Oklahoma where 39 federally recognized tribes from across the continent reside; which Indians are allowed to wear headdresses?

“From New England down to the south, with what became the ‘five civilized tribes’ of Oklahoma after their removal, there weren’t headdresses as we know them. There was feather adornment on head gear, but very typical headdress that has been been and portrayed in Westerns is very plains-centric,” explained CPN Cultural Heritage Center Director Kelli Mosteller, Ph.D.

The mixing of tribal traditions has a long history in Oklahoma. Indeed, one of the Citizen Potawatomi’s

most famous members, artist Woody Crumbo, grew up with members of other tribes. His art and success as an artist were ultimately influenced by these experiences. Mosteller sees that drive to label

what is pure Potawatomi teachings from other tribes’ traditions as a fairly recent phenomenon.

“People in the early twentieth century were practical. This is where they lived and these were the people they lived next to. Teachings, techniques, traditions; you pick up from these places and people. We as Potawatomi started to incorporate more things with the buffalo that were down here, because there certainly weren’t a lot running around northern Indiana.”

Even Potawatomi bands like the Citizen Potawatomi and the Prairie Band developed different traditions, dating back to the pre-removal area. While the former were primarily based in the northern woodlands on the shores of Lake Michigan, the latter’s traditional territories further west brought them into contact with the plains’ tribes.

“When they ended up on the same Kansas reservation together after the removals, it was two different tribes with different practices that were occupying the same area,” said Mosteller.

Oklahoma’s role as the last stop for many North American tribes provides a study of the impact that intermarriage and close quarters can have on tribal cultures. Though mixed tribal families in areas like the Great Lakes aren’t uncommon, many tribes in those areas share common cultural practices. The Odawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi are a perfect example. The diverse geographic origins of so many Oklahoma tribes means that a child might have a mother who is a descendent from the Potawatomi, originally from Indiana, and a Cherokee father, whose ancestors originally lived in mountains of North Carolina.

In Europe, similar geographic distances would likely bring one into contact with two different cultures, languages and possibly, countries. Though the Potawatomi did not traditionally use what is commonly

thought of as a traditional headdress, wearing one should be done with respect for the culture from which it came. Mosteller pointed out that while disrespect may not be intended, someone from a tribe who holds such items sacred might not see it that way.

“For someone whose headdress is a sacred item, like the Lakota Sioux, they may not understand why you were wearing it,” she said.

However she also cautioned that even if someone is wearing a headdress, that doesn’t mean they may not have permission or the blessing to don it.

“There are times when someone is gifted a headdress from a member of a tribe with those traditions, and they are wearing it respectfully as a gift they received. You never know a person’s story. So the onus is on the wearer ultimately to be respectful and know why they are wearing it.”

What did they wear?

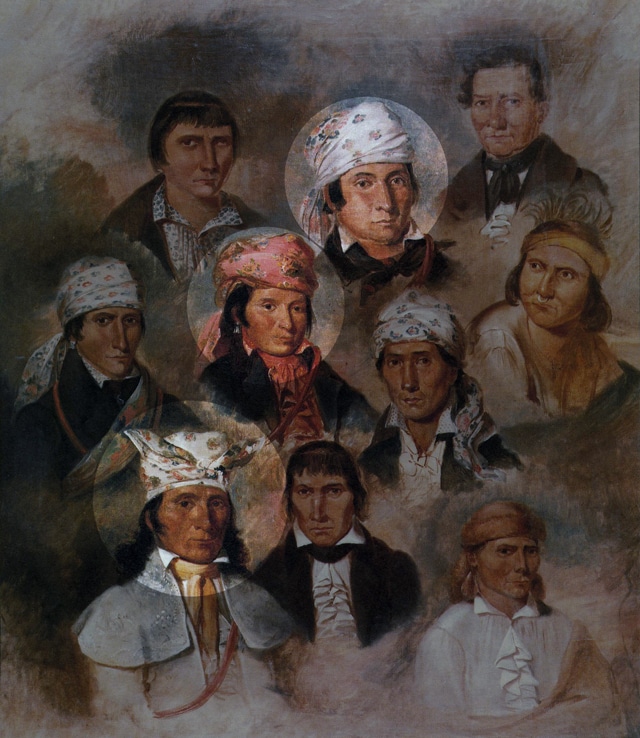

For the Potawatomi today, their forefathers’ headgear may not be as practical in the Oklahoma summers as it was when the Tribe resided further north. Turbans – made from cloth and before their near extinction from overhunting, otter and beaver skin – were a common adornment on Potawatomi men in the early years of European contact. Looking at the sketches of famous Potawatomi chronicler George Winter, one often sees more turbans than not.

In an 1837 journal entry, Winter described the dress of Jean Baptist Brouillette, an Indian interpreter who was half Canadian and half Miami.

Wrote Winter, “His tout en semble was unique, as his aboriginal costume was expensively shewey [sic]. He wore around his head a rich figured crimson shawl a la turban, with long and flowing ends gracefully falling over the shoulders.”

As noted in historian Robb Mann’s “True Portraitures of the Indians, and of Their Own Peculiar Conceits of Dress,” Winter’s description of Broullette’s dress reflected what was characteristic of male dress in the Great Lakes fur trade society.

“Many men wore colorful silk scarves wrapped around their heads to form turbans and most wore trade silver earrings,” wrote Mann.

The ornate dress of the Potawatomi in many of Winter’s sketches indicates that not only were they and their neighboring tribes doing well during the booming fur trade years, many were also dressing the part.

In her work “Indian Women and French Men,” Susan Shepler-Smith writes the artist’s portraits “are the visual evidence of the prosperity that characterized indigenous communities in the southern Great Lakes.

Nor were the more elegant figures in Winter’s portfolio dressed for ceremonial occasions; theirs was the dress of daily life.”

Mosteller pointed out that there are some discrepancies on the origin of the turban in Potawatomi culture, saying several stories have been debated in recent years. She noted one version in which a delegation of Cherokees visiting the eighteenth century court of the King of England were told to look more presentable by their English hosts before their meeting.

Finding their uncovered heads unsuitable, the English courtiers found disused turbans left behind from a previous delegation visiting from the Indian subcontinent. Upon the successful meeting wearing the turbans, the Cherokees returned to North America where the cloth turban’s popularity grew along the North American trade routes, with the Potawatomi ultimately catching up with the trend.

“The thing is, the cloth turban might have happened that way, but the Potawatomi were already wearing otter skin turbans. Just looking at it practically, with cloth you don’t have to hunt it, clean it and then wear it. Cloth was more practical,” said Mosteller.

Practicality remains a common theme with the Potawatomi today and their neighboring tribes, wherever they may be. With 32,000 members spread across the U.S. and Canada, it’s only natural for traditions, dress and practices to intermingle. As with all things, the goal is to remain respectful and cognizant of the meaning of cultural items one dons.