By Allison Herrera, KOSU Invisible Nations

The below article was written and broadcast for KOSU Radio’s Invisible Nations. It is reproduced here with its author’s permission. See the original article here.

Soldiers returning from battle face special challenges. Thousands suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and their care can be more involved and long-term. The nation’s VA hospitals, although under recent scrutiny, will care for more than a million of the nation’s soldiers.

But, the nation’s Native American veterans face a set of extra challenges after fighting on the front lines.

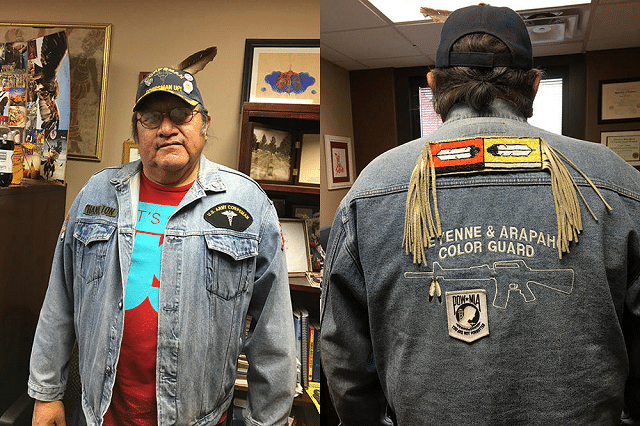

Matheson Hamilton was a state side medic serving at the Presidio during the Vietnam War where he saw a lot of soldiers tragically wounded and die. When he returned to Oklahoma in 1977, he started drinking to cope with the things he saw. To get sober, he tried a number of different programs, including Alcoholics Anonymous, but nothing worked.

“Dealt with it the best way I could. To get to sleep at night, I’d get drunk. I thought it was sleep, but I was just passed out. I’d wake up and the first thing I want to do is get drunk again so I don’t have to think about things.”

Then he found the Warriors group, a special substance abuse program at the Oklahoma City VA hospital aimed at Native veterans. It started in 1999 when the VA decided it wanted to better serve two population of its veterans: women and Native Americans. The program was the first of its kind in the country.

“Through friends of mine they said, ‘go to the warriors group. It’ll help you out a whole lot.’ And I got back into the ceremonies after I joined the Warriors group. Started going to sweats and did the sundance. Just got my life back on the right road.”

He’s been sober for eight years now. He says it was Susan Vaughn, one of Warriors group founders who helped him stick it out.

Vaughn started as a licensed social worker at the VA in 1997. When she was approached to start the Warriors group, she quickly learned that this program needed to be different. Rather than sitting in group talking and processing like Alcoholics Anonymous, these Native veterans wanted to be active and give back to the community. She says it’s the key to the program’s success.

“I think the cultural piece of that is that they wanted to be very involved with their families and the community. Pow Wows. We started the pow wow in 2000 because they wanted to give back. The guys went up on the floors and got veterans in wheelchairs and brought ‘em down to the dance and it was wonderful.”

The Veterans Honor Dance at the Oklahoma City VA Hospital is now in its 16th year. Participants from the Warriors group and the Elders council—an offshoot from the Warriors group—honor veterans both living and fallen. Gifts are given, songs are sung and a Grand Entry rivaling that of any major Pow Wow takes place in the VA’s auditorium.

At this year’s Veterans Honor Dance, they honored Candy Klump, who is leaving the VA this month to care for another veteran: her dad, who fought in World War II. Throughout her time at the VA, she’s gained new respect for Native Americans who serve our country.

Candy Klump begins her day like any other at the VA hospital in Oklahoma City—making the rounds, chatting with hospital friends and offering up words of support. We’re walking towards the ER to see a patient Candy helped admit after he complained of serious pain. We arrive to find him lying on his side waiting to for the ER doctor to check him out.

Klump has been with the VA for 27 years, and her goal is simple: help Native American Veterans get the care he or she needs.

It turns out that may be more complicated than you think-that’s because Native veterans face an extra set of challenges. They have more health issues before serving their country and, according to the VA’s own 2015 study, they serve their country at higher rate than other veterans.

And then there’s the cultural piece-family and community are a big part of people’s lives in Indian country. So are ceremonies, which serve as an extra layer of protection when dealing with war time trauma.

“If you see a veteran sitting in a room and they see another veteran there and they get to talking, there’s a camaraderie and there’s a connection there will not be between any other two people in the room. Well, if you get Native American veterans in a room and they get to talking, that is even double. To me, Native American veterans are a sub-culture of a sub-culture.”

Since 2013, Klump has worked exclusively with Native veterans after the VA signed an agreement with Indian Health Service to streamline the care they receive. It’s a big deal if you live far away from the nearest VA facility. Klump’s job is a lot of cutting through the red tape so vets can have easier access to care. The main issues are transportation, making sure that veterans know they’re even eligible for care and communication.

In addition to her rounds at the hospital she gives trainings to non-Native staff about how to talk to Native vets, whose communication style might not be what they’re used to.

“A Native person may not look you in the eye. It doesn’t mean he’s lying. A Native American person if you tell them no, is probably not going to come back and ask you again.”

Native veterans still seek a lot of their care from the VA hospital, which doesn’t plan on ending the unique services for this special class of veterans. And even though Candy Klump is leaving the VA, the program she helped start and the work she did will continue.

You can interact with Invisible Nations and provide your own experiences by texting the word “Press” to 405-759-8336.