After the Potawatomi arrived in present-day Kansas, Indian agents R.W. Cummins and A.J. Vaughan established a pay station and trading post at Uniontown located south of the Kansas River and west of present-day Topeka, Kansas. The settlement served as a commercial hub for Tribal members, and its position along the Oregon-California Trail made it a popular stop for those moving west.

“We not only re-supplied horses and oxen, we also sold food supplies, grain, repaired tools and sold tools and utensils. Uniontown also offered travelers access to a doctor and blacksmith” said historian and Citizen Potawatomi Nation District 4 Legislator Jon Boursaw.

“Uniontown was very transient,” said CPN Cultural Heritage Center Director Kelli Mosteller, Ph.D, during a recent tour of Uniontown. “Legally, no one was supposed to live here but us and our families. If they were living here, they were having to do it with the permission of the Tribe. They were not able to receive annuities and the different things under our treaty rights.”

Westward expansion

Uniontown boasted 60 structures at its height, and stories indicate 19 were saloons, Boursaw said.

“The saloons also had hotel rooms on top of them, so most people who were coming through were not long-term residents,” Mosteller said. “Those passing through might stop to get more supplies and trade goods.”

The Kansas Historical Society estimates 300,000 traveled along the Oregon and California trails. This brought an influx of people through Uniontown, and many went through the settlement before crossing the Kansas River.

In Uniontown, the Potawatomi often bought pianos, stoves and other large items from people traveling west.

“At this point in the trail travelers realized that these items weren’t going to make it all the way,” Boursaw said. “We either used them in our own homes, sold them locally or barged them to as far east as St. Louis and sold them to travelers heading west to do it all over again.”

Besides commerce, those migrating west also brought deadly diseases along the trails including cholera and smallpox, which negatively impacted the Potawatomi. A cholera outbreak hit Uniontown in 1849.

“They literally burned the town,” Boursaw said. “We had no immunity to it. Native Americans across the country, throughout North America, had no immunity to cholera and smallpox.”

Today, a large cottonwood tree marks the mass grave of at least 22 to 35 Potawatomi who lost their lives during the outbreak.

“It has been said that they were all buried in a circle with their heads pointed to the tree,” Boursaw said. “Many more, possibly hundreds, are thought to be buried in the fields that surround the tiny cemetery.”

The sickness drove away some looking to make Uniontown a permanent residence, but it did not slow the traffic along the two trails. By 1852, Uniontown became the largest settlement in present-day Kansas, but by the end of the year, another cholera outbreak devastated the community.

“Uniontown was technically burned twice — I don’t think it was fully burned the second time around,” Mosteller said.

“They burned specific districts.

“They didn’t fully understand that cholera was transmitted through water and things like that,” Mosteller continued. “Burning it gave the water time to filter itself through. They did know that if you burn it, abandon it and come back later, the cholera is gone. They didn’t understand that they could have done it without burning the town down if they would have just given the water system a break to let it go through its natural filtering cycle.”

Beyond fire

Uniontown was also an experiment by the federal government to place two Potawatomi groups — the Mission Band (which later became the Citizen Potawatomi) and Prairie Band — together on one reservation through the Treaty of 1846. The Mission Band arrived in Kansas on the Trail of Death, and the Prairie Band initially removed near Council Bluffs, Iowa.

From 1847 to 1859, the Potawatomi from both bands received their annuity in Uniontown. Most lived in the vicinity, and in 1849, records indicate 3,235 Potawatomi arrived for the spring annuity payment.

The government paid Native Americans specific sums of money and supplies over the years as compensation for the Native lands taken through treaties.

Tom Ellis reported in Uniontown and Plowboy – Potawatomi Ghost Towns: Enigmas of the Oregon-California Trail, “The Kansas River created its own stresses. The Potawatomi north of the river, including the Prairie Band, complained about crossing the river to receive their annuity payments and petitioned for their own pay station, blacksmiths, and traders. Conflict also developed over the concept of ‘national debts,’ a decades-old practice of allowing traders to incur debt on behalf of the tribe and be directly reimbursed by the Indian agent. This put considerable power in the hands of traders and chiefs the traders favored. The government began giving annuities directly to individual Indians, thus diluting their impact on any one trader and further dividing the centralized power within the tribe by both chiefs and the traders they favored. Citizen and Prairie Bands favored different traders, so the concept of concentrating them at Uniontown fell apart.”

Bourassa cemetery

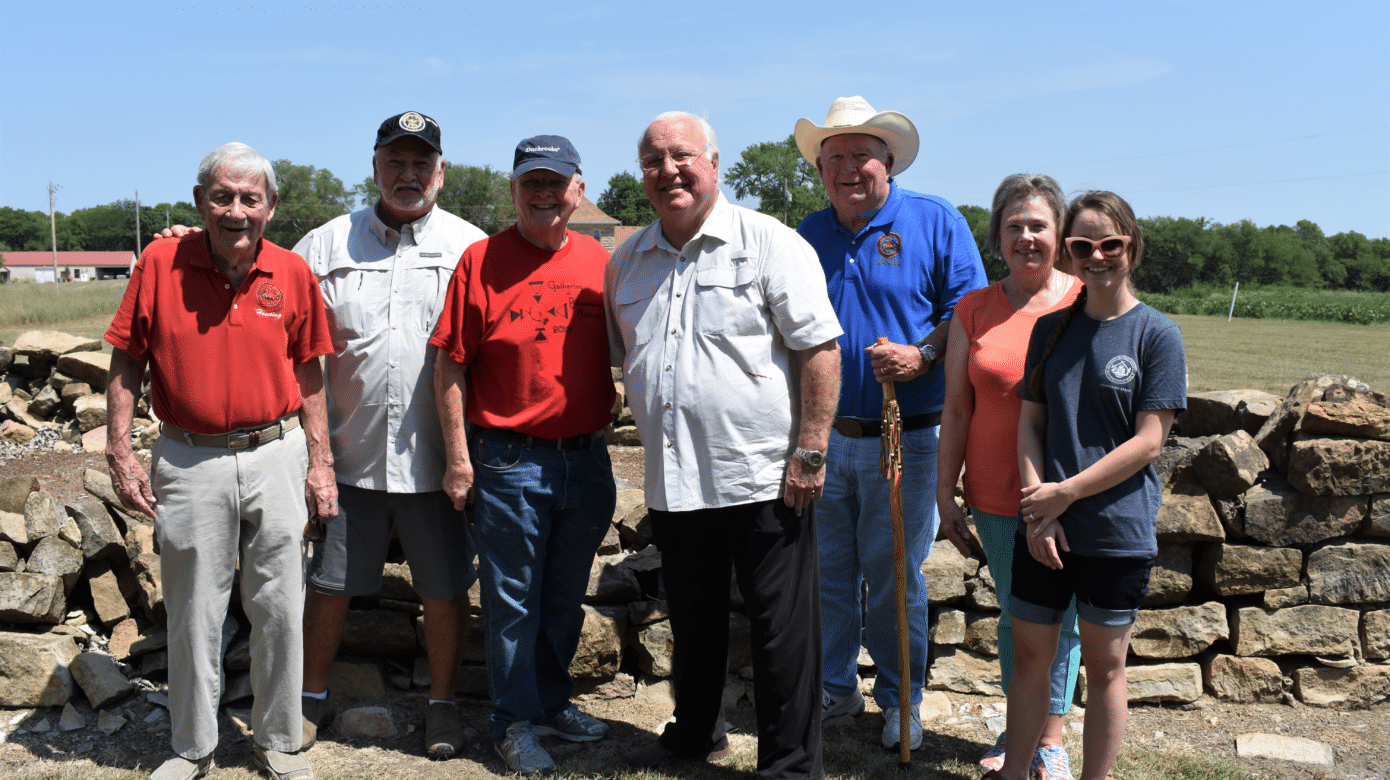

After Uniontown no longer served as the Potawatomi Pay Station, it ceased to exist. Uniontown once bustled with businesses and people, but today only a cemetery remains with three areas encapsulated by stone walls. Two include marked graves, and one surrounds the Potawatomi mass grave under the cottonwood tree.

“This site is the family of Joseph Napoleon Bourassa, my great-great-grandfather,” Boursaw said, then pointed to the farthest north section on the property.

While very little relics remain beyond a few headstones, the Green family built a home from Uniontown’s remnants, which still stands to the north of the cemetery.

In 2010, the National Park Service recognized Uniontown on its National Register of Historic Places for its significance in Potawatomi, U.S. and Shawnee County, Kansas, history.