By Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton

Betty Nicholson would rather not have anyone follow in her footsteps.

Nicholson is a coordinator for the Citizen Potawatomi Nation diabetes program. She is also a diabetic and did not know how to handle the disease for six years.

“No one told me how to manage my diabetes until I started teaching this class,” she said, referring to the Tribe’s Beginning Education About Diabetes course.

In an effort to lower the number of cases and the rate of prediabetes, November has been designated as Diabetes Awareness Month.

Nicholson is one of the estimated 30 million American adults who have diabetes. Up to one-quarter of that number are unaware that they have the disease, and an additional 86 million have prediabetes, a condition where a person’s blood sugar is elevated beyond healthy levels but not to the point to indicate diabetes. If left unchecked, prediabetes can lead to full-blown diabetes as well as an elevated risk for strokes and heart attacks.

Most diabetics have Type 2, or insulin resistant diabetes, where the pancreas makes insulin to convert food into energy, but the body’s cells are unable to use it effectively. If untreated, the glucose from food winds up building up in the blood stream rather than getting to cells as needed.

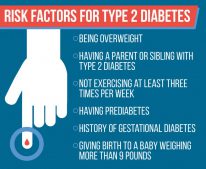

Although the condition can be caused by genetics, it is more frequently due to external factors such as obesity, poor diet, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and smoking.

Multiple studies have shown a correlation between the disease and an increased intake of corn syrup and other refined carbohydrates, a common ingredient in many low-cost, shelf-stable processed foods.

Type 1 diabetes is when the body does not produce insulin at all. It accounts for 1.25 million cases nationwide with about 40,000 new diagnoses annually.

A third form of the disease, gestational diabetes, occurs in almost 10 percent of all pregnancies. Like Type 2, it is a form of insulin resistant diabetes and can increase the risk of high blood pressure during pregnancy. About half of the women who develop gestational diabetes go on to have Type 2 diabetes postpartum.

Virtually unknown in Indian Country until the 1950s, diabetes is now more than twice as common among American Indians and Alaska Natives as the general population. Once known as adult onset diabetes, the current incidence rate of Type 2 diabetes among Native American youth is estimated at almost 50 diagnoses per year for every 100,000 teens — more than double that of any other group.

Oklahoma has one of the country’s highest rates of diabetes across all racial and ethnic groups, with 12.7 percent of all adults diagnosed with either Type 1 or Type 2. Almost 17 percent of Indigenous adults in Oklahoma are diagnosed with the disease.

To combat the high rate of diabetes, CPN offers a five-session program for people recently diagnosed, plus annual follow-up sessions. Participants meet with public health nurses, a dietician, a primary care provider and other staffers from the Tribe’s health department. They discuss proper nutrition, exercise and elimination of potential complications from the disease including blindness and poor blood circulation.

“Prevention is the key,” Nicholson said. “If people will realize that if they keep their blood pressure and blood sugar in the normal range, they can prevent a lot of the complications we talk about.”