During a November tour of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center, director Kelli Mosteller, Ph.D., noted the removals that impacted Tribal members’ ancestors happened over the course of decades, not centuries.

“It’s distinctly possible that someone born in the woodlands of Indiana who made the march along the Trail of Death and lived in pre-Civil War Kansas ended up in Oklahoma after 1872,” Mosteller said.

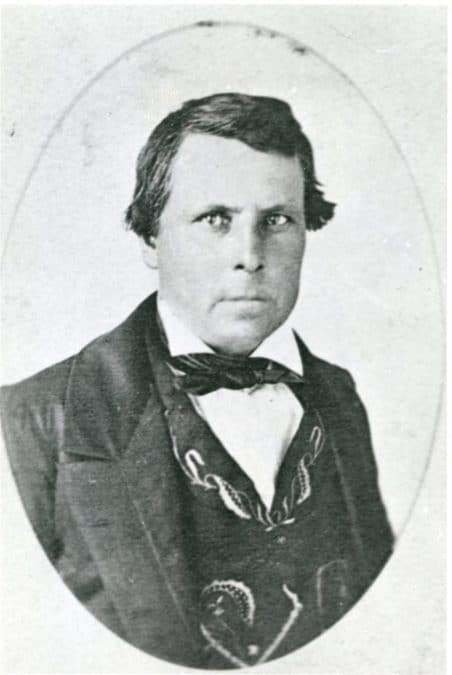

The removals forced the Potawatomi south from their ancestral homelands in Indiana and rippled across the lifetimes of hundreds of individuals. Though he never made the journey to the Tribe’s current home, one member used his language skills and education to speak for the Potawatomi during the mid-1800s.

In March 1810, Joseph Napoleon Bourassa was born in the Great Lakes region to Daniel Bourassa II and Theotis Pisange. Early historical records list him as Ottawa. This was likely due to a family baptismal record sheet listing his mother as Chippewa-Ottawa, though other records note that her husband was also Potawatomi and Chippewa.

Joseph, known for his affinity for languages, heard and spoke English, French and Potawatomi at a young age. Early on, he became known as “Bourassa the Interpreter” and served as a translator during councils and treaty negotiations between the United States government and tribes.

He unfortunately lived through the harsh results of those negotiations. In 1837, he was on a removal conducted by George H. Profitt. Only a year later, his family suffered further.

They lived in Chief Menominee’s village along Indiana’s Yellow River in 1838 when American militia forced the community to abandon their homes and begin what became known as the Trail of Death. Both of Bourassa’s parents died in the years immediately following their removal from Indiana along with several of his brothers and other close relatives.

Bourassa attended Carey Mission School in Michigan and Hamilton College in New York. Eventually, according to Bourassa’s writings, he transferred to the Choctaw Academy of Kentucky to study law in the early 1830s.

Choctaw Academy

The academy originally opened in 1819 by the Kentucky Baptist Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Heathen. It soon ran short of funds, closed and then reopened in 1825 on the property and under the direction of Richard M. Johnson. By the time it reopened, the Kentuckian gained a nationwide reputation as the man who slew Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader, at the Battle of the Thames during the War of 1812.

Not coincidentally, Johnson benefited from the school’s formation. His brother-in-law, William Hurd, oversaw the Choctaw Nation in Mississippi and notified the politically connected Johnson of a request from that tribe.

Choctaw leaders wanted the U.S. to create an institution that would train Choctaw students in the ways of the white settlers who were using every means possible to dispossess the Choctaw of their lands. Under Johnson’s direction, the academy’s curriculum focused on reading, writing, surveying and arithmetic. Other academic pursuits included music and language education.

While the institution initially served only Choctaws, Johnson’s political connections quickly increased the academy’s attendance to other Native Americans. U.S. Indian agents funneled money and students from across the West to the school in Scott County, Kentucky, at the expense of tribes they oversaw.

The Potawatomi were amongst those who sent students. Johnson discussed an incoming class that would be enrolled in the school after the signing of the Treaty of Chicago.

“Genl (sic) Tipton and Gov. Cass who will make the treaty are here, (and) they have promised me pointedly, that they will secure a literary fund like the one upon which we are now acting (and) I will recommend the Pottawattomies (sic) to send so many scholars as will come to our school,” Johnson wrote.

The school operated on the infamous 19th century ethos of “civilizing” Native Americans. The uprooting of young men from their families and traditional homes did not always go well. Johnson wrote of having to send home several “expensive and troublesome” Potawatomi at one point.

Bourassa found success at the academy, exemplifying the institution’s ideal student. He learned how to operate in the whites’ world in hopes of one day representing the Potawatomi in its dealings with the U.S.

After graduation, he taught there and at other institutions including an all-male Jesuit school, which he listed as his employer on an 1840 record.

He applied his education while developing one of the first Potawatomi dictionaries with a Potawatomi alphabet written during the Tribe’s time in Sugar Creek, Kansas.

Potawatomi leader

Bourassa, partially due to his education and language skills, was a known figure in the Potawatomi leadership circles. Along with his brother Jude, he signed the 1846 treaty with the U.S. He is noted as a representative of the Wabash, St. Joseph and Prairie Bands of the Ottawa, Chippewa and Potawatomi Indians on the document.

Yet in some historical accounts, his role in Kansas is a controversial one. In the years preceding the Civil War, disagreements arose between Native Americans forcefully removed to the 34th state. The Prairie Band and Citizen Band forged ahead on two different paths when it came to the issue of individual land allotments. The former sought to hold onto their bountiful, heavily timbered reservation in communal holdings. The latter, hoping for a better future laid with rights enshrined as U.S. citizens, accepted allotments in anticipation of prospering off their individual land holdings.

White authorities from railroad companies seeking to lay lines across Potawatomi reservations as well as federal government officials sought common leadership amongst the two nations to help decide the matter, presumably in their favor. Owing to the fluid nature of inter-band Potawatomi ties, Bourassa ascended to leadership positions through relations with the federal government. In 1861, he was seated as a representative of the Prairie Band on the combined bands’ business committee.

Though listed as such in historical records, the business committee idea was likely a push by federal officials to make sense out of the confusing — in their eyes — structures of Potawatomi governance in Kansas. Those named to the committees along with Bourassa largely had common, Western education backgrounds and were put forth by Potawatomi headmen as committee members for that reason.

Historian William E. Unrau labels Bourassa as a “government-appointed chief;” a front for corrupt Indian agents and railroad speculators who wanted the Potawatomi land for a future line west.

In one instance, he claims that Bourassa only “married in to the tribe.” The pointed insinuation makes him sound like a white interloper who came to the Potawatomi mostly to take advantage of land deals.

The Ojibwe, Potawatomi and Ottawa were common people: Nishnabe. Intermarriage between tribal peoples and whites was common in the centuries before Bourassa’s era. In terms of inter-band dynamics at play while in Kansas, Bourassa may have faced challenges due to his Métis status with French and Indian heritage. Due to his mixed heritage, he may not have had access to “traditional” leadership pathways. Though he had been present and active in tribal governing affairs for some time, his ascendency to the business committee provided an opportunity to help shape his people’s future using the skills he learned from his education at American schools.

There was definitely a split in the opinions of members of the Prairie and Citizen Potawatomi when it came to allotments and other issues; these differences were not unique to their time.

Along with several other Potawatomi leaders, Bourassa signed the 1861 treaty that gave the Citizen Band U.S. citizenship and individual land allotments, breaking up their communal reservation. Bourassa and his family — like other band members — received land allotments with the signing. The agreement came with a catch though: the government kept full ownership rights entirely out of the Potawatomi’s control until a time when the United States decided the Indians were competent. This meant that the Potawatomi were citizens in name only, given no true rights to their land aside from the ability to sell it to speculators. Most succumbed to losses via taxation, which the Kansas state government insisted upon as part of the treaty’s approval.

Though Unrau refers to the Prairie Band Potawatomi’s refusal to take allotments admirably — until it was forced upon them by the 1887 Dawes Act — his criticism of Bourassa seems harsh. History proved that no tribe was immune from the encroachment of American settlers regardless of the path they chose. All Kansas-based tribes lost their original communal reservations in some form or another before the century ended.

Citizen Band leaders like Bourassa likely realized this during the early 1860s as Potawatomi landowners sold or lost their shares to non-Indians.

A letter from Bourassa in 1866 about white encroachment echoes this sentiment, noting the complicity of American authorities in turning a blind eye to treaty violations:

“It seems to me the course taken in settling our affairs, being so slow, is in breaking the law.”

His tone indicates the peril that Potawatomi leaders faced as the U.S. again turned its eyes westward after the Civil War. It saw Indian people only as encumbrances against the spread of Manifest Destiny. This was likely the future Bourassa and other Citizen Band leaders saw when signing the 1867 treaty that provided their people a place in Indian Territory.

Walking on

Bourassa never made the journey to Oklahoma despite helping set the terms of the Citizen Band’s move there. This was likely due to his success and stature in Kansas, having become well-known in Indian and white communities in and around the Topeka area.

His ties to the Potawatomi grew deep as he aged, having been wed four times to Tribal members throughout his life. First in 1838 to a woman named Memetikosiwke. Upon her passing, he wed Mah Nees. His third wife was Mary E. Nadeau who passed away in 1872. Finally, he wed Elizabeth Curlyhead.

Well-known Potawatomi chronicler George Winter recorded Bourassa in his early life, prior to the removal to Kansas. Winter noted a woman named Quehmee accompanied Bourassa to Kansas, and there is some speculation that her name may be an abbreviation for Memetikosiwike.

He was still reportedly in good health as he traveled the Kansas communities with a priest in October 1877. Yet, he was overcome by what was described as “lung fever” while at his younger sister Elizabeth Chilson’s house a few miles outside of Rossville, Kansas. He died there on Oct. 29, 1877.

“The old gentleman’s demise was quite unexpected,” read the St. Mary’s Times obituary for Bourassa, “as he was in town for a few days before his death apparently in robust health, and telling of the sport he was having duck shooting.”

Walking on with Bourassa was another sliver of the Tribe’s physical connection with its homelands in the Great Lakes.