Friday, March 29, will mark the second anniversary of the signing of the Vietnam War Veterans Recognition Act by President Donald Trump. The act designates March 29 of each year as National Vietnam War Veterans Day, an event honored by people nationwide to commemorate the sacrifices of veterans of America’s second-longest conflict.

Native American servicemen and women have long been a backbone of the American military, serving the U.S. Armed Forces at a higher rate, per capita, than any other ethnic group. According to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, approximately 42,000 Native Americans served during the conflict. While disagreement about the United States’ participation in the war peaked at home, 90 percent of Native American service members in the Vietnam Era were volunteers.

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center’s Wall of Honor has a section dedicated to the service of Vietnam veterans. Many of the active members of the CPN Veterans Organization served during the war as well.

According to records available at the Cultural Heritage Center, more than 250 Citizen Potawatomi served during the conflict. To date, it was the largest enlistment of the Citizen Potawatomi for any conflict involving the U.S.

Though many served, below are two brief profiles of Citizen Potawatomi veterans of the Vietnam Era. If you are a veteran of any armed service during any time and have not done so, please contact Blake Norton at the CPN Cultural Heritage Center to ensure your place on the Wall of Honor.

Dennis Hoy

Dennis Hoy was a private first class on March 20, 1967, as his company engaged with a numerically superior enemy force in the village of Tan An. The 5th Cavalry Regiment’s rifleman company set up a blocking position under heavy enemy small-arms fire coming from a tree line and the village’s structures. He returned fire from an exposed position, killing several enemy soldiers.

Amid the combat, several of Hoy’s comrades were seriously wounded and under intense fire themselves. He repositioned himself to a more exposed spot on the battlefield and provided enough covering fire to allow his fellow platoon members to rescue their comrades.

The recommendation order for the Silver Star he was awarded for his actions noted, “Hoy’s action contributed significantly to saving several lives. His gallantry under fire is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflects great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.”

Hoy returned to the U.S. and held various jobs before settling full time into a career as an artist, and many of his works reflect his time serving in Vietnam. He currently resides in New Mexico.

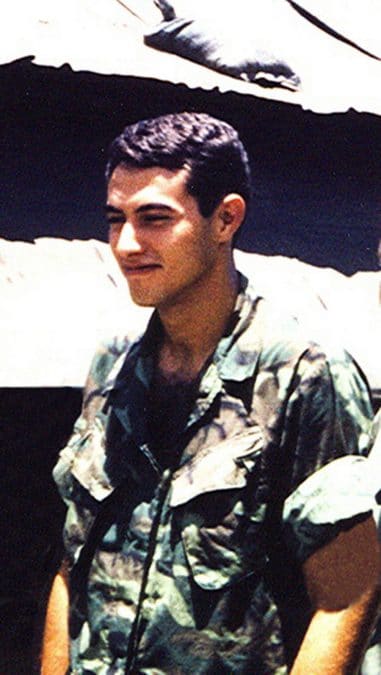

Randy Herrod

Randy Herrod arrived in Vietnam less than two years after his high school graduation in Calvin, Oklahoma, in 1968. Herrod’s 3rd Marine Division was stationed in one of the most hotly contested theaters in the war at the time, just outside Da Nang, and officer Oliver North was his first platoon commander.

North, who picked up the nickname “Blue” because the Corps’ designates the color for the direction north, lead a group of marines who became known as “Blue’s Bastards” while in combat against the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong irregulars.

Herrod received credit for saving his officer’s life at one point, rescuing North as he lay exposed to fire after being felled by a percussion grenade. Though North recommended him for the Silver Star, a high-profile murder trial took precedence in the Citizen Potawatomi marine’s life.

In March 1970, Herrod faced first-degree murder charges in connection with the extrajudicial killings of 16 villagers — mostly women and children — on Feb. 19, 1970. He was eventually acquitted after the defense team, led by Oklahoma State Senator Gene Stipe, proved Herrod’s patrol had come under fire before discharging their weapons. North flew back to Vietnam to take the stand in his defense as a character witness and as an investigator despite having left the country before the incident.

Herrod eventually received the Silver Star for his actions in saving North and other Marines July 8, 1969. Though suffering from wounds received in combat that wiped out half of his company, Herrod assumed command of a machine gun and routed a charge by oncoming Viet Cong soldiers.

Herrod was honorably discharged from the Marines and spent time working in the oil fields before taking on a career as a police officer. Eventually he opened a chain of karate studios across the Midwest.