Members of the Kickapoo and Potawatomi tribes lived near one another in the days of pre-colonial settlements in the Great Lakes region. Those connections continued through the removal period, with both peoples removed to separate states before landing in both Kansas and Indian Territory.

Even today, the descendants of the two peoples continue living close to one another. The headquarters of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma are only a few miles apart, both groups leaving Kansas in the decade after the Civil War while a few holdouts remained.

Another connection between the groups may also exist and hold the key to a curious 1863 Potawatomi census record denoting a particular set of enrollees as “Mexican Pottawatomies.”

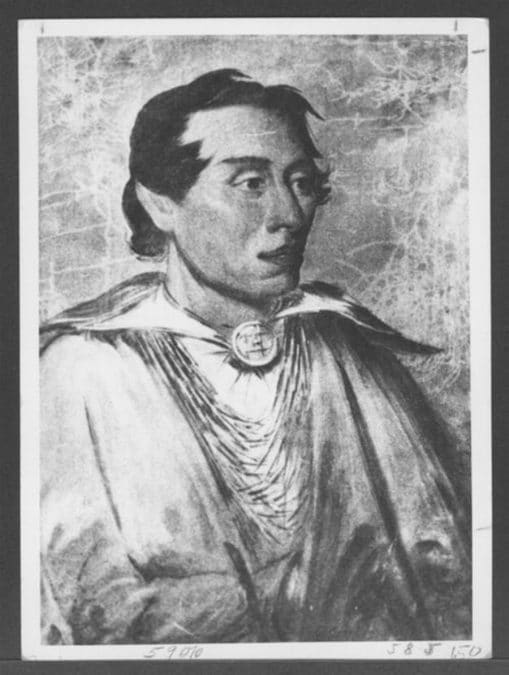

Kickapoo Prophet

As the United States emerged as a distinct and unified nation under President George Washington, tribes along the northwestern frontier territories of the current-day Midwest faced collisions with white settlers.

A man named Kennekuk, known as the “Kickapoo Prophet” was believed to have been born near the present town of Danville, Illinois, in the 1790s. Amidst the encroachment of white settlers in the Kickapoos’ traditional homelands between Lake Erie and Lake Michigan, he built a reputation as a religious thinker and developed a unique philosophy for fellow tribal members.

The growth of religious and cultural philosophies across Indian Country to counter the losses experienced as a result of American Manifest Destiny was not unusual. The most well-known example is the uprising of the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa, who with his brother Tecumseh, led a major military campaign with members of numerous Indian nations against the U.S., before ultimately failing at the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe.

A convert to Methodism and an ordained minister in the faith, Kennekuk’s approach mixed some western and traditional beliefs but eschewed Native Americans from educating their children in American schools. He bridged his viewpoints with a foundational principle in the abstinence of alcohol. His concepts drew nearby Potawatomi while still in Illinois, and those connections likely continued during the Kickapoos’ first removal to Missouri, and later, Kansas.

According to a report from Commissioner on Indian Affairs, the tribal leader ingratiated himself by treating the Nishnabe converts as equals, writing that “Kennekuk was determined that they should enjoy the same privileges as the Kickapoos. The Kickapoos and Pottawatomies (sic) signed an agreement in 1851 which allowed the sharing of annuities and spelt (sic) out arrangements for equal rights. The two groups intermarried and confused the bureaucrats who now worried about sorting them out for census purposes.”

Because of this, the government cut off annuity payments in 1847 to the Potawatomi who refused to rejoin their tribe’s reservation along the Kansas River. A Potawatomi headman named Nozhakum insisted upon remaining with the Kickapoos.

The relationships between the Potawatomi and Kickapoo continued during those times, both with those who lived with the Kickapoo and those in the Mission Band and Prairie Band. Kennekuk’s teachings also forbade selling their lands, instructing that it was a violation of the Great Spirit’s commands. This position likely drew support from Potawatomi who opposed the tactic of accepting U.S. citizenship and individual land holdings. Located near present-day Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, Kennekuk’s band, known as the Vermillion Kickapoo, successfully took up agriculture incentivized under the Treaty of Castor Hill.

The success of those agricultural operations and the group’s prime location as a Kansas waypoint for further American expansion to the West may have led to leadership disruptions. When Kennekuk died from smallpox in 1853, the presence of the Potawatomi likely exacerbated tensions. According to a George Schulz article in Kansas History, “It appears that Kennekuk intended Wansuk, a Pottawatomie (sic) to be his successor.” Another account by Joseph B. Herring noted that Nozhakum inherited the mantel of spiritual leadership after the Kickapoo Prophet’s death. In either case, the accounts demonstrate the enduring ties between the Potawatomi and their adopted group, despite the ties remaining with the other Potawatomi reservations in Kansas.

Like all the tribes in North America, the land assigned to the Vermillion Band came under increasing pressure from white encroachers in the decade before the U.S. Civil War. What was initially a reservation of 768,000 acres dwindled to 150,000 the year after Kennekuk’s death, leading many of the Vermillion Band to coalesce in a small town named for their leader that was a way station along a route of the Pony Express. By 1862, the once vast Vermillion Kickapoo lands measured only 6 square miles.

Faced with increasing violence between pro and anti-slavery forces in Kansas, along with little help from federal authorities regarding dilution of their lands, a portion of the band resolved to move once again. Around 1862, they went south to Mexico where some of their brethren traveled in the 1830s after losing their original Missouri reservation along the Osage River. These Kickapoo and Potawatomi left Bleeding Kansas behind them, with former allotments and property still held in their names.

Mexican Pottawatomie

Under the leadership of a Kickapoo named Nokoaht, the group was relocating south when they passed a small stream near present-day Mertzon, Texas. The group — likely confused with Comanches, the most prominent raiding tribe in Texas before the Civil War — was followed by a unit of Confederate forces and Texas militia.

The resulting engagement became known as the Battle of Dove Creek. Though the Kickapoo and Potawatomi group were peaceful, the Anglo forces mistook their advantage of surprise. In the initial assault on the Indian camp, a frontal assault resulted in the deaths of three officers and 16 enlisted soldiers. According to Nokoaht’s telling in the years after the fight, around 15 from his group perished.

It was a lopsided defeat for the combined Confederate and Texas militia forces, which likely facilitated another decade of cross-border recrimination from the Kickapoo and Potawatomi group once they settled in Mexico.

However, despite their absence, these members were noted as Citizen Potawatomi landholders in the 1867 treaty. Other members took their land holdings via court order. In charge of chasing down those who might have been part of the Mexican-based group was Citizen Potawatomi leader Joseph Napoleon Bourassa.

Bourassa served as a translator, business committee member and treaty signer throughout Tribal affairs in Kansas. He was a prominent player in the Tribe’s history during that era, and it was under his direction that the Potawatomi sought to find out who perished during the battle at Dove Creek.

Correspondence with an officer whose soldiers took part in battle shows Bourassa attempted to track down any casualties inadvertently listed as Kickapoos.

In September 1866, Bourassa, identified as an interpreter for the Topeka Agency, wrote to Colonel John B. Barry, an officer involved in a later engagement following the battle.

“About two years ago, a party of our people went South, or towards Mexico with a party of Kickapoos. And I heard they had a big fight with the Texsans (sic), and killed about 60 or 70 of them; though I learned, they fought on the defensive, at that time — And I am informed, that, they came back to Texas, to take revenge of that fight, and they all got killed … I am the United States Interpreter, and a relative of some, that, are reported to have been killed. It will be a great relief to us to learn the particulars…”

He was, in all likelihood, chasing down the leads of Potawatomi who were listed on the 1863 allotment roll as “Mexican Pottawatomies” (sic). According to Fr. Joseph Murphy’s Potawatomi of the West: Origins of the Citizen Band, “These were Indians who, along with elements of the Prairie Band, went off to Mexico with the Kickapoos. The Sac and Fox Agency records, Indian Territory, make it clear that some of these later joined the Citizen Band on the Oklahoma Potawatomi reservation.”