The Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center provides resources to keep the Tribe’s history safe and accessible for generations to come. One key way the Nation does this is through the CHC’s archives. To highlight some of these holdings, the Hownikan is featuring photographs and family history of every founding Citizen Potawatomi family. If interested in assisting preservation efforts by providing copies of Citizen Potawatomi family photographs, documents and more, please contact the CHC at 405-878- 5830.

Arrival in North America

The Beaubien family’s roots in North America begin with fur trader Bertrand Farfard Suier de La Frambois. He married Marie Sedilot in Three Rivers, Canada, on Dec. 20, 1640. Together, they had a son named Jean Baptiste. The family moved from Quebec to Vermont and New York. Jean wed Francois Marchand, and their son Jean Baptiste LaFrombois III married Genevieve Trotier La Bissoniere. Jean III and Genevieve lived near Lake Champlain during the Revolutionary War. One of their sons, Francois LaFramboise, moved near Lake Michigan in the late 1700s and married a Potawatomi woman named Shawenoqua. They had four children, including Joseph, Francois, Alexis and Josette (LaFramboise) Beaubien.

Joseph LaFramboise was born near the Saint Joseph River around the year 1799. The family eventually settled in Chicago, and Joseph and his father Francois became some of the first voters in the city. Joseph married Therese (Theresa) E. Peltier. During the Black Hawk War in 1832, Joseph served alongside British-Potawatomi fur trader Billy Caldwell — Sauganash. He and Theresa had a large family, and Joseph rose to prominence as a Tribal leader alongside Chief Wabaunsee and others.

Land loss and removal

On Sept. 26, 1833, the Potawatomi signed the Treaty of Chicago, which ceded more than 5 million acres of land in return for money, goods and a reservation west of the Mississippi. Joseph’s name appears on the treaty. A few years later, Joseph and his family removed to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where he served as a leader until the Potawatomi moved to a new reservation in Silver Lake, Kansas, in 1846.

Joseph’s daughter Theresa married Allen Hardin at the age of 14. The marriage dissolved, and she then married Thomas Watkins who served as the first postmaster in Chicago. Stories recount that the city’s elites attended the lavish wedding, including Native warriors dressed for battle.

According to an article published in 1974 by the Los Angeles Times, “Watkins had invitations printed repeatedly until he was forced by the number of requests to attend to invite everyone who was anyone in Chicago to the ceremony.”

However, the marriage ended in divorce. Theresa eventually met and wed Madore Beaubien on June 2, 1854, at the Baptist Mission in Mayetta, Kansas. Madore had made the move west with a group of Potawatomi in 1840 and served as an interpreter.

Between the three marriages, Theresa had 13 children: Madaline Watkins, Joseph Watkins, Louisa Watkins, Mary Hardin, Therese Hardin, Peter Hardin, Philip Beaubien, John Baptiste Beaubien, Julia Beaubien, Rose Beaubien, George Beaubien, Peter Beaubien and Rose Ann.

Beaubien

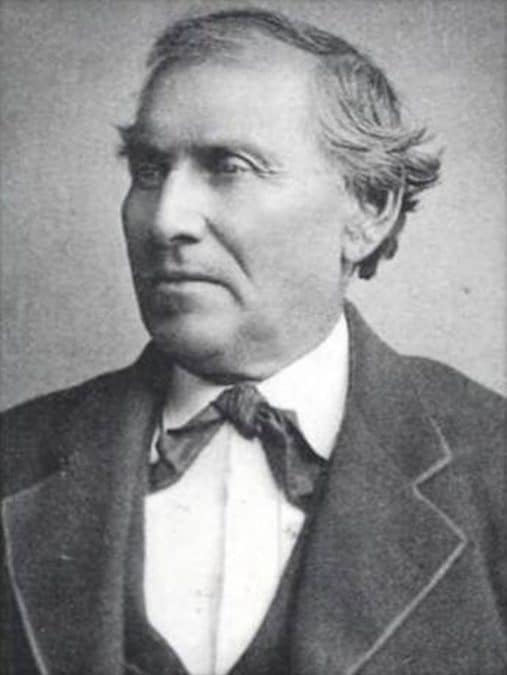

The Beaubien and Potawatomi connection officially began with Madore and Theresa’s marriage. Madore was the son of Jean Baptiste Beaubien who moved the Chicago area after the Battle of Fort Dearborn in 1816.

Jean Baptiste was a well-known fur trader, learning the business from Joseph Bailly. He married an Ottawa woman named Mahnawbunnoquah and had two children: Charles Henry and Madore. He then married Josette LaFromboise, daughter of Francis, further connecting the two families.

Although Jean Baptiste visited Fort Dearborn before the historic battle in 1812, he did not establish his home there until the U.S. Army finished rebuilding the fort. He then became an American Fur Company agent and continued the family fur trade business, traveling all across the Great Lakes region. According to the City of Chicago’s first tax roll in 1825, Jean Baptiste was the town’s wealthiest man. Even after the fur trade declined, Jean Baptiste refused to leave the city. He rose to prominence, becoming a leader across Chicago and held a reputation for being an ally to many Native Americans.

Upholding his father’s leadership traditions, Madore joined numerous Potawatomi tribal leaders and Indian Agent William Ross in 1861 on a trip to Washington D.C. to seek senate approval of the Treaty of 1861. The treaty provided the Potawatomi an opportunity to become U.S. citizens and official landowners under American law. This was appealing to some who saw it as a chance to own property and obtain a sense of permanency and protection from white encroachment. Numerous Beaubien received allotments in Silver Lake, Kansas, near the Kansas River.

Like the treaties of the past, the federal government did not uphold the 1861 agreements and began collecting taxes before the two-year grace period ended. As a result, the government took Potawatomi farms and allotments to then sell to white settlers and traders for a large profit.

The three decades in Kansas proved daunting for the Beaubien family and Potawatomi alike. Not only did the Tribe have to figure out how to survive as Eastern Woodlands people on the prairie — they experienced large-scale deaths due to disease, continued land loss and negative federal policies, including assimilation, acculturation and allotment. In order to continue as Citizen Potawatomi, Tribal leaders began looking for opportunities outside of Kansas to build new, better lives.

Due to a clause in the 1861 treaty, Citizen Potawatomi sold what remaining lands they had in Kansas to purchase a new reservation in Indian Territory. Eventually, Beaubien descendants moved to present-day Oklahoma and received allotments.

Theresa and Madore’s children and grandchildren expanded the family connections, adding Hardin, Allen, McEvers, Bostick, Ogee and more last names still recognized by Citizen Potawatomi today.

If interested in helping preserve Citizen Potawatomi history and culture by providing copies of family photographs, documents and more, contact the Cultural Heritage Center at 405-878-5830.