The Oklahoma land runs remain some of the most notable events in the state’s history. The six that took place between 1889 and 1895 helped pave the way to statehood in November of 1907. Many people associate them with a feeling of excitement in the air as pioneers and cowboys waited to claim their new property in uninhabited land. However, the reality was much starker.

“Each one was a bigger disaster than the next,” said Dr. Kelli Mosteller, director of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center. “Human nature comes into it. There’s greed. Land greed made the worst of human nature come out. You had fights. You had people shooting each other. You had Sooners who were sneaking in and taking the plots of land and cheating.”

The first land run took place on April 22, 1889, and established present-day Oklahoma City and Guthrie in one day. The Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s historical ties are with the Land Runs of 1891, which took place on Sept. 22, 23 and 28. They resulted in the founding of two new counties — “County A” and “County B” — later named Lincoln County and Pottawatomie County.

“Surplus” and “unassigned”

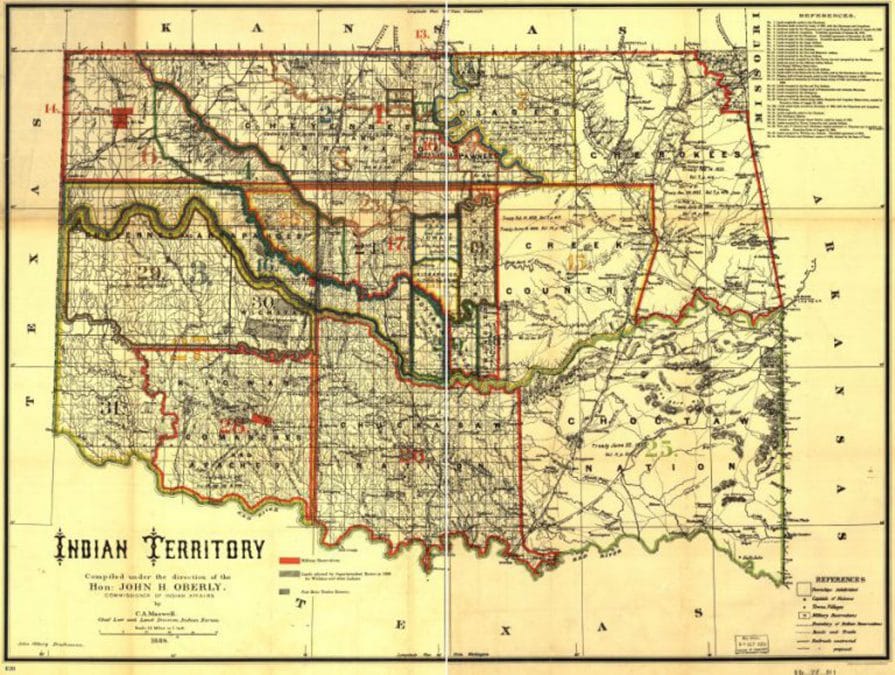

The U.S. government forcibly removed many tribes to Indian Territory following the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, with the Potawatomi taken from their homelands to Kansas during the Trail of Death in 1838. After the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act of 1862, encouraging independent farmers to move west.

“The Homestead Act basically said that if you move onto a plot of land and you take care of it and improve it over five years, at the end of that five years, the title is yours,” Dr. Mosteller said. “There was a precedent for this idea of people moving in and taking land without having to pay for it and eventually becoming the titleholder to that land.”

The Citizen Potawatomi signed the Treaty of 1867, which resulted in Tribal members selling allotments in Kansas to purchase a new reservation in present-day Oklahoma. Over the next decade, members moved and took allotments across the new reservation. Then, the Dawes Act of 1887 authorized the subdivision of communal Native reservations throughout the United States. After all Citizen Potawatomi — young and old — received plots of land, the government deemed the remaining acreages as “surplus land” or “unassigned land” for settlement during the land runs.

“We did not think of it as surplus land. We may have understood that it was presently unsettled land, or that it was land that we, in that moment, weren’t using in a way that our Indian agent or others who were moving in thought it should be used. It may not have been under cultivation. It may not have been fenced off. There may not have been a home on it, but that does not mean that we did not understand that this is ours by treaty and by purchase,” Dr. Mosteller said.

The Homestead Act and the Dawes Act’s ramifications meant the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma, Sax & Fox Nation, Citizen Potawatomi Nation and Absentee Shawnee Tribe owned a vast majority of land, either by individual members or as part of a reservation, that was then settled by outsiders during the Land Runs of 1891.

“The concept of moving non-Natives in and letting them seize land and call it their own was well established in American history, but the method of the land run was something fairly new,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Some historical accounts of Sept. 22, 1891, claim more than 20,000 people lined up in various locations surrounding the settlements, waiting for the starting signal to stake their claim. More lined up the following day for a second land run, which settled Tecumseh as the seat of “County B.”

“We’re just watching over half of our reservation disappear into non-Native hands in one afternoon, and there’s nothing we can do about it,” she said.

Citizen Potawatomi Nation began purchasing back original allotments in the 1970s to re-establish and expand its sovereignty as a Tribe.

“It has cost the Tribe a great deal of money, buying back our former reservation lands one acre at a time. It’s a huge expense. … The stripping away of tribal lands raised questions about control and jurisdictional boundaries that have been ongoing for decades now,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Reenactments

Representations of land runs in popular culture show a misleading series of events and often dismiss Indigenous people.

“If you’ve ever seen the movie Far and Away, it’s just acre upon acre of rolling hills, and no one’s there, and that really was not the reality for most of the land runs. … They were having to checkerboard through these settlements of all of these tribal people who had been there for 20-plus years at that point,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Public school curriculum, both in Oklahoma and across the country, fails to discuss Native American land’s dispossession. For some elementary students, one of their first lessons in Oklahoma history includes a reenactment of the Land Run of 1889. Dr. Mosteller refers to the oversimplification of Oklahoma’s statehood as a “disservice” that lends itself to the idea of Manifest Destiny.

“I think when you try to (teach) it without complicating that history and making it more three dimensional and fleshing it out and putting in all of the complicated stories and all of the people who were on the other end of these pioneering efforts, you are doing a disservice because we can love our country, and we can be proud of our country, only when we truly understand what happened in the United States and how our history played out,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Learn more about the history of Citizen Potawatomi removal and displacement by visiting the CPN Cultural Heritage Center. The Indian Territory: A Place to Call Our Own gallery includes an interactive exhibit outlining the geographic effect of the Land Runs of 1891. Visit cpn.news/gallery9 for a video presentation of its offerings.

For further learning opportunities, read about the Native Knowledge 360 Degree education initiative from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian at cpn.news/360NN. In Oklahoma, visit cpn.news/OKCPSNASS for curriculum resources from the Oklahoma City Public Schools Native American Student Services.