Feb. 8, 2021, marks 134 years since President Grover Cleveland signed The Dawes General Allotment Act. This policy divided tribal land into individual holdings, and it included provisions for opening the leftover plots to non-Native settlement. As a result, tribes across the United States lost 62 percent of their land, or approximately 86 million acres, which included large swaths of the Citizen Potawatomi reservation in present-day Oklahoma.

“It served the larger purpose because the larger purpose was twofold: to make us more like white people or destroy us and get large amounts of land out of Native control and into the hands of individual, non-Native citizens,” said Dr. Kelli Mosteller, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center director.

While the Dawes Act did not impact every tribe in the United States, it affected a tremendous number of Native Nations within the central Plains region, including most that call Oklahoma home. Settlers wished to hold property and establish farming and ranching enterprises on the fertile lands between the Rocky and Appalachian Mountain ranges. The Dawes Act provided the groundwork needed to meet these requests and encouraged agricultural development.

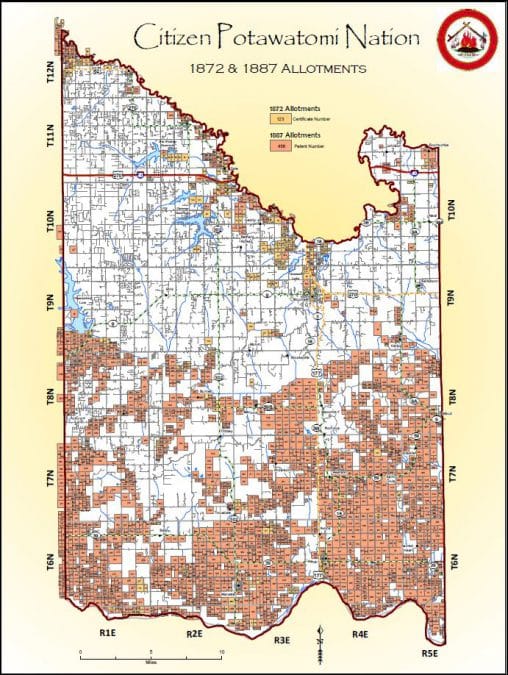

Through the act, Citizen Potawatomi received allotments based upon age and family standing: 160 acres for heads of households, 80 for unwed adults and 40 for those under 18. The Potawatomi reservation included portions of present-day Pottawatomie, Cleveland and Oklahoma counties, and many Tribal members chose plots in the southern and northern-most portions of the 900-square-mile reservation.

Not the first “rodeo”

The Dawes Act was not the Nation’s initial experience with the allotment process. The Treaty of 1861 served as one of the federal government’s earliest experiments with providing Native Americans individual plots of land to then open the remaining acres for non-Native settlement. However, within a few short years after signing the treaty, a great number of Tribal members soon found themselves landless due to the federal government’s refusal to fulfill agreements.

Through the Treaty of 1867, many Citizen Potawatomi members that still possessed their properties sold them to purchase a new reservation in present-day Oklahoma. In 1872, the Tribe went through another round of allotments on the new reservation. Although some Citizen Potawatomi received plots of land in 1872, the Nation owned the surplus acres.

“By 1887, this was our third allotment for the Citizen Potawatomi,” Dr. Mosteller explained. “We had done this. We knew what we were getting into, but with the Dawes Act, there was nothing we could do.”

The 1861 and 1872 allotment processes provided opportunities for the Citizen Potawatomi to voice their concerns to the federal government, but the Dawes Act did not. Approximately 1,600 Citizen Potawatomi received plots of land through the 1887 legislation.

“It was not a panacea — a cure-all — for the ‘Indian problems’ that the federal government touted it to be, and they absolutely knew that,” Dr. Mosteller said. “They argued that this would make life better for Native people, but they knew that was very likely not going to be the case.”

Oklahoma statehood

Although originally touted as Indian Territory — lands set aside for only Native Nations for as long as the grass grew and the water flowed —the Dawes Act laid the groundwork for Oklahoma to become an official state.

“Opening up land in Oklahoma for non-Native settlement and the Dawes Act were happening in tandem. The Dawes Act was brought here to make that possible,” Dr. Mosteller said.

After the Dawes Act, the Citizen Potawatomi owned only one-third of the original reservation its members purchased outright through the Treaty of 1867. The federal government deemed the remaining two-thirds surplus land that non-Native settlers eventually had a chance at owning.

Three years after the Dawes Act, the Organic Act of 1890 opened up “Unassigned Lands” and established boundaries for the formation of Oklahoma Territory, which included almost all of present-day Lincoln, Payne, Logan, Oklahoma, Canadian, Cleveland, Kingfisher and Pottawatomie counties. It also opened up the panhandle — known as the Public Land Strip or No Man’s Land — and the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache, Cheyenne-Arapaho, Osage, Otoe, Kaw, Ponca, Pawnee and Wichita-Caddo reservations.

“The Organic Act of 1890 set up this whole concept of non-Natives moving in and that it wasn’t going to be this ‘Indian Territory’ that we were fighting for,” Dr. Mosteller explained.

Land runs began in 1889. Hopeful landowners lined up to stake their claim to the un-allotted reservation properties. The Citizen Potawatomi and many other tribes witnessed large portions of their reservations officially change possession within a matter of hours.

“The Dawes Act solidified once again the distrust that has settled in about dealing with the government. Every time the government comes in and asks for something, there is always that ulterior motive,” she said.

“But also, I think another impact it had on us was the whole concept of ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.’ It made us very tough, and all of the things we went through before this was building toward this moment.”

Tribal members used past experience to work with the federal government to receive as much money as possible from the surplus, or unassigned, land. Although the returns were still far below actual value, the Citizen Potawatomi never stopped fighting for the Nation’s sovereignty.

“They had to bear down and make the best out of an often not only bad situation but an uncertain situation — an uncertain future. There was a lot of resilience and that spirit of ‘push on to the next day.’ … A lot of people refer to it as a ‘pioneer spirit,’ but I think more accurately, it’s a spirit of people who understand that they don’t know what tomorrow brings and to make the most of today,” Dr. Mosteller said.

Learn more about The Dawes Act and its impact on the CPN by visiting the Cultural Heritage Center’s gallery Indian Territory: A Place to Call Our Own or online at potawatomiheritage.com.