The plink plink, plink plink of maple sap dripping into metal buckets every spring sings a sweet song to Barbara Wall’s ears.

“It’s just one of those feelings, you know?” Wall asked. “After a long winter, you’ve got the warm sun on your face, and you can hear the sap drip into the buckets. It just makes me want to dance.”

Wall is a descendant of the Vieux family and is currently finishing her Ph.D. in Indigenous studies, while holding a tenure-track position in the Chanie Wenjack School for Indigenous Studies at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada.

Late winter into early spring during the Maple Sugar Moon is one of her favorite times of the year. Wall bundles up and heads to the bush to tap maple trees, collect sap and transform it into ziwagmedé (syrup) and zisbakwet (maple sugar). The Nishnabé people use the thirteen moons of the seasonal cycle as guideposts, yet because of the varied ecosystems and weather conditions across Nishnabé communities, some may recognize each moon at a different time. For many, the Zisbakwtoke Gises (Maple Sugar Moon) begins on February or March’s new moon.

“From my teachings, when the sap runs, that’s the beginning of the new cycle of the seasons and the Nishnabé new year,” Wall said during a phone interview with the Hownikan.

Wall grew up in northern New York and has enjoyed maple trees throughout her life. She often spent her youth in the woods behind her family’s home, letting the maples provide guidance to her adolescent woes.

“I’ve always had a connection to maple trees and appreciated their beauty,” she said. “As a teenager, I’d go out, and sit, and even lay on my back on the ground and look up through the maple trees, and they’d kind of bring me peace.”

For the past 10 years, Wall has called Ontario home, and the sugar bush season has been a mainstay for her every spring.

“You really get to know the trees. And you get to understand their cycle, their seasonal cycle, and how they look. And not just the leaves, but how the bark looks. And how the bark looks just before the sap runs is different from what the bark looks like in the deep part of winter,” Wall said.

Maple’s gifts

According to Wall, as winter comes to a close, maple sap is the first nutritional gift from the earth, and it is used as a sacred medicine and cleanser.

“Thinking back to when we really lived off the land rather than living out of grocery stores, toward the end of the winter, the supplies might be running low,” she said.

During winter, Nishnabé diets were comprised mostly of meat and mnomen (wild rice) in wild ricing communities.

“So, the sap would clean us out and prepare our bodies to start eating more plant-based foods,” Wall explained.

According to Justin Neely, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Language Department director, oral traditions surrounding maple vary from community to community. One in particular, Nanabozho and the Maple Trees, notes that a long time ago, syrup ran from the trees in the spring, not sap. The Nishnabé people were not tending to their duties, rather spending all their time under the maple trees, consuming the rich, sweet syrup. Seeing this, a powerful spirit — Nanabozho — decided to pour water into the trees, which diluted the sap and required hard work to enjoy its sugary bounty once more.

“The story has varying teachings inside, when you think about it,” Neely explained. “It’s telling you that you have to take care of your priorities. You can’t just fixate on one thing. You have to do these things when the time arrives.”

In some Nishnabé communities, women are the ones who oversee the sugar bush because of maple sap’s connection to water. Care and protection of water are key responsibilities for Nishnabé women, yet harvest and processing requires everyone’s involvement.

“Having maple sugar camps is very common where everyone kind of comes together, and always, as a community, we believe in sharing and helping those that are maybe less fortunate,” Neely added.

Before colonization, Nishnabé families returned to specific sugar bushes annually, and for those who are able, the traditions continue today.

“And it was also a time when the community would start to come together, whether it’s extended family that’s working the sugar bush or several families getting together,” Wall said. “It’s a time of coming back from the isolation of winter to being back in more of a social environment.”

While the moons provide guidance or instruction for when to begin tapping, Wall also looks for signs from the animals and the maple trees themselves.

“The crows fly south in the winter — ravens are here all winter, but the crows leave — and when they come back, they start to gather; that’s when you start to pay attention to the maple trees,” Wall said. Squirrels will also break off small branches, and woodpeckers pierce the trees to ingest the sap.

Wzhek’ge (to tap a tree)

Before tapping a tree, it is an important practice to ask for permission and place sema (tobacco) down as an offering.

“Some people will do this at every tree they tap,” Wall explained in a video produced at Trent University for the National Center for Collaboration in Indigenous Education. “Others will just do it at the first tree that they tap. But it’s a small gesture of reciprocity — of giving thanks to the tree for all that it’s giving to us as Anishinaabeg.”

Many use their left hands in making sema offerings, as the left arm and hand connect directly to the heart. “This is where you speak the truth — your left side and through your heart,” she said.

Tapping a maple tree in a traditional manner requires using an axe or another similar tool to make shallow cuts into the bark of the tree trunk. The initial cuts create a V shape before crafting a horizontal indentation at or near the bottom of the V.

The last cut is “parallel to the ground, but it’s at an angle so that the sap will run down,” Wall said. “The size of the cut isn’t necessarily as important, in my opinion, as the angle.”

After making the three cuts, harvesters place a cedar spile; the spile directs the flowing zisbakwtabo (maple sap), letting it run down into a folded wigwas (birchbark) container — wigwas nagen. This method usually results in debris like twigs and leaves entering the sap, but the outcome is sweeter than using modern techniques.

“It’s gentler on the tree because it doesn’t go as deep as the metal spigots,” Wall said. “Also, people who work in sugar bushes have shared with me that the sugar concentration of the sap is higher closer to the outer bark of the tree than towards the inside of the tree.”

Filtering the sap before placing it in another container more suitable for travel eliminates contaminants. Wall said harvesting birch bark to create maple sap-carrying buckets happens during the winter when the dormant trees’ bark becomes thicker.

After filtering the zisbakwtabo (maple sap), some then utilize a yoke placed around their necks to carry the birch bark buckets full of maple sap out of the bush.

Modern tapping utilizes a power tool to drill, which creates a hole to hammer a metal spigot into.

“The tree will heal, but the old style tapping is a more sustainable type of tapping,” Wall said. The shenamesh (maple tree) heals more quickly from a shallow axe cut than a drilled hole.

Process and storage

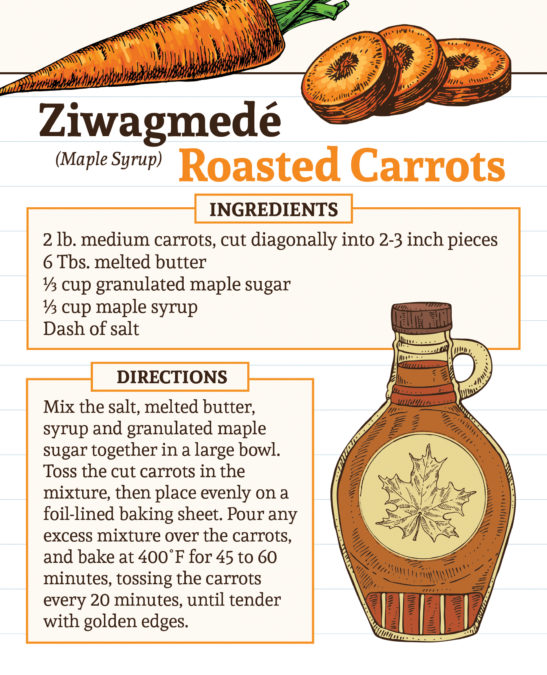

After harvesting, boiling the zisbakwtabo (maple sap) evaporates the water, concentrating the sap. This also helps develop the deep, rich flavors synonymous with ziwagmedé (maple syrup). To make syrup, often a wood shkode (fire) is kept going under pans or pots of raw sap.

“Depending on the season, it takes a ratio of 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup, and then it’s almost a 1 to 1 ratio on the syrup to the sugar,” Wall said. Typically, sugar is larger than the volume of syrup.

Making zisbakwet (sugar or maple sugar) requires heating the syrup in a mkek (pot) until it reaches the thread stage, which is approximately 223 F to 235 F.

However, Wall prefers to use observation rather than a thermometer. “It’ll go through stages where (the heated syrup) foams up, then it will quiet down. Then the bubbles will get bigger, and it’ll foam up again,” Wall explained. “It requires a lot of patience and observation.”

Cooking the syrup evaporates additional water, and once it reaches the optimal consistency, Wall pours the molten sugar into a bis’egéwnagen (sugar trough). Then she begins to move the mixture back and forth with wooden sugar paddles that help with the cooling process. The movement and manipulation of the molten sugar alters its physical form.

As it cools, “it changes from the molten liquid to more of a runny mud and then a fudgy kind of material,” Wall said. “And then you keep working it, and then you end up granulating the sugar. If you do it right, you’ll end up with granulated sugar that’s just as fine as the white sugar that you buy in a store.”

Before the Nishnabé had access to glass, plastic and other materials to store maple syrup, they primarily created granulated sugar that they placed in naturally-made containers.

“It was a major trade product between communities, but also, once the fur trade started, a lot of maple sugar was shipped over to Europe. It was a source of sugar for the queens and kings in Europe,” Wall said.

Future of maple

Although colonization has created limited access to maple for Nishnabé — especially the Citizen Potawatomi whose land base in Oklahoma does not provide suitable growing conditions for sugar maple — it still serves as an essential connection to Nishnabé culture. Maple sugar is incorporated into dishes for feasts and is a key component of many ceremonies.

Wall enjoys the ancestral connection that she finds out in the bush while making syrup and sugar.

“I know there’s a sugar rush, but it’s almost a reconnection rush that happens too,” she explained.

However, environmental changes are negatively impacting sugar maple populations across North America. Sap flows best when air temperatures reach around 40 F during the day and below freezing at night.

“As the climate warms, we might not have that specific range of temperatures, so maybe the sap will no longer flow in the amounts needed for production of syrup and sugar,” Wall explained.

While access is still available, Wall encourages all Citizen Potawatomi to try real maple syrup or sugar themselves.

Consuming maple syrup and sugar is “a move forward, but it’s also a move backwards and a reconnecting with ancestors. It’s reconnecting to what our bodies remember,” Wall said.