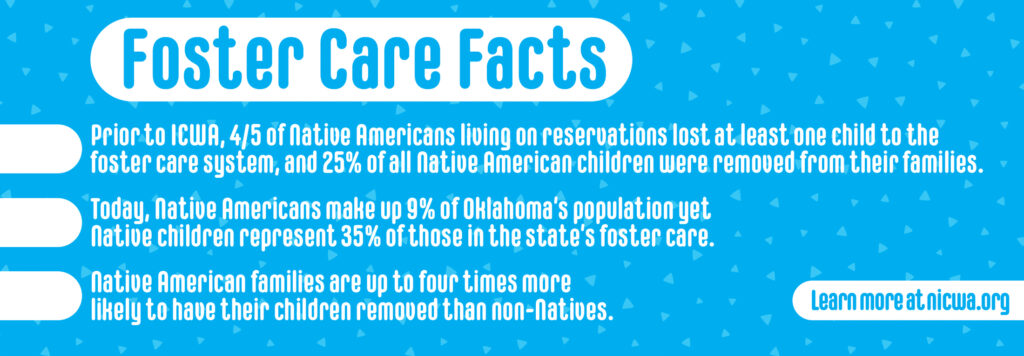

Native Americans are up to four times more likely to have their children taken and placed into foster care than their non-Native counterparts. Oklahoma Department of Human Services reported in 2020 that Native children represented more than 35 percent of those in foster care, yet Native Americans make up only around 9 percent of Oklahoma’s population.

“That is the definition of racial disproportionality,” said Citizen Potawatomi Nation FireLodge Children & Family Services Foster Care/Adoption Manager Kendra Lowden.

While the Indian Child Welfare Act has existed since 1978 and provides added protections, numerous factors continue to impact the unequal rate of Native American representation within the foster care system.

Need for ICWA

Before 1978, approximately 80 percent of Native American families living on reservations lost at least one child to the foster care system, according to data compiled by National Indian Child Welfare Association. Additionally, more than 25 percent of all Native children were removed from their families, with 85 percent receiving placements outside of their tribes or relatives.

“And that was even if there was no abuse — there were no issues occurring,” Lowden said. “Even if there were willing and fit family members available, these children were still adopted out to white families.”

These policies continue to negatively impact individuals, families and tribes. Non-tribal placement and adoption has created identity issues and disconnected feelings along with negative mental health outcomes.

“They may be living in a community where they’re the only Indian person, and when people feel stress, anxiety, depression, a lot of times they cope in unhealthy ways, and that is in order to mask their trauma,” she said.

Past federal efforts including forced removal, boarding schools and more contribute to inherited trauma, which can have destructive effects on Native American family units and their dynamics.

“Historical trauma … is passed down emotionally, psychologically, internally and also externally,” Lowden said.

ICWA attempts to decrease the number of Native American children that are removed from their communities and culture, helping ensure the future is brighter and healthier. It sets requirements for states to work directly with Native Nations and establishes specific standards before removals occur. However, the law is not always followed or understood.

Post 1978

Placing children and facilitating adoptions with Native families, especially those from the same tribe, mitigates some of the long-term outcomes that resulted from policies prior to ICWA; however, many states remain non-compliant.

“Part of that reason is there are no legal repercussions,” Lowden said. “So if a state does not follow the law or have their workers work with families in the way that the law outlines, they are not going to get their funding pulled. … There is not a huge incentive for states to follow it, especially if they don’t have strong partnerships with tribes.”

According to an OKDHS report released in September of 2020, 7,774 children were in Oklahoma foster care, and 322 were in tribal custody. Yet, of the 7,452 in state custody, 2,567 were Native American.

“Despite the extraordinary number of American Indian children in custody in Oklahoma, foster/adoptive parents do not currently receive substantial training about the Indian Child Welfare Act or how to care for the unique, individual needs of American Indian children,” Lowden said.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs released Guidelines for Implementing the Indian Child Welfare Act in 2016 to provide resources, references and more to assist with implementing and upholding ICWA.

“There is positive progress that is being made,” she said. “But there are other issues that impact ICWA, including media misrepresentation, so people have the wrong idea about the law and how it helps families.”

In response to the need for knowledgeable and improved reporting, the Native American Journalists Association developed Recommendations for Reporting on the Indian Child Welfare Act.

“Some ICWA cases may be newsworthy, however, the way journalists report ICWA stories can encourage anti-Indian sentiments and influence negative behavior toward tribes and tribal citizens,” the guide stated.

Key NAJA recommendations include never referring to blood quantum, protecting child privacy, reaching out to tribal experts, and understanding the law is not based on race.

“This perpetuates the false idea of the law being unfair compared to other races and ethnicities. Indian status is not ‘racial’ but rather ‘political’ as a matter of law,” Lowden said.

Solutions

OKDHS data indicates more than 80 percent of Oklahoma’s foster and adoptive homes are not Native American, but the likelihood of having a Native child placement is high. While the state requires training to become a foster or adoptive parent, Lowden believes ICWA-specific instruction and tribal consultation can assist foster and adoptive homes to better meet the needs of Native American children in their care.

“Since the current OKDHS foster/adoptive parent training pre-service curriculum lacks substantial ICWA training, it is very likely families will feel lost or unsure of how to connect children to their heritage,” Lowden said.

Preventing children from entering the system may be as simple as being a good neighbor, friend or relative.

“You should always report child abuse and neglect whenever you suspect it, but there’s a lot of things that community members can do to assist families and prevent bad things from happening,” she said.

This could include helping get children to school or providing contact information to potential resource providers.

“Offering support to people and not judging them is key,” Lowden stressed. “It can’t hurt to offer, and that may be the one thing that family is needing to hold them together is just somebody to support them. And, it can really change the dynamic of everything.”

FireLodge Children & Family Services has numerous programs to help prevent family separation as well as ones to get guardians back on the right path.

“There are many times that when a parent becomes involved with child welfare, that’s the first time they have ever been offered help. It’s the first time that they’ve been able to realize that some behaviors are problematic or are not helpful, so they get engaged in therapy and parenting classes and learn the skills they were not able to due to their raising or the environment that they’ve been in,” she said.

When CPN becomes involved in child welfare cases, FireLodge Children & Family Services’ number one goal is reunification.

“As long as it’s safe and appropriate, being with their family is really how a child’s identity develops,” Lowden said. “If we can keep a child with their family, we don’t disrupt their identity or what they’re learning about themselves.”

FireLodge assigns a skilled and qualified staff member to each case. These individuals work one-on-one with families and build relationships that are critical to long-term success. Lowden also sees the department’s work as a way to uphold CPN’s sovereignty.

“The reason that we do become involved in every case is we care about the families. We don’t want any Potawatomi children lost from the Tribe,” she said.

“We’re trying to undo what was done to us, and there’s still a long way to go when we still have a very disproportionate amount of American Indian children in foster care compared to other races. But, we are seeing good things happen.”

Learn more about FireLodge Children & Family Services by calling 405-878-4831, or check them out on Facebook @CPNFireLodge.