After removal west of the Mississippi, the Potawatomi utilized the limited available resources to survive. The Tribe’s expedition to present-day Missouri and Iowa put them in first-hand contact with other groups also experiencing displacement, including Mormons, and the Tribe fell back on their trade and commerce knowledge in order to thrive.

Platte Purchase

Discourse between the Potawatomi and the Platte Country began through the 1833 Treaty of Chicago.

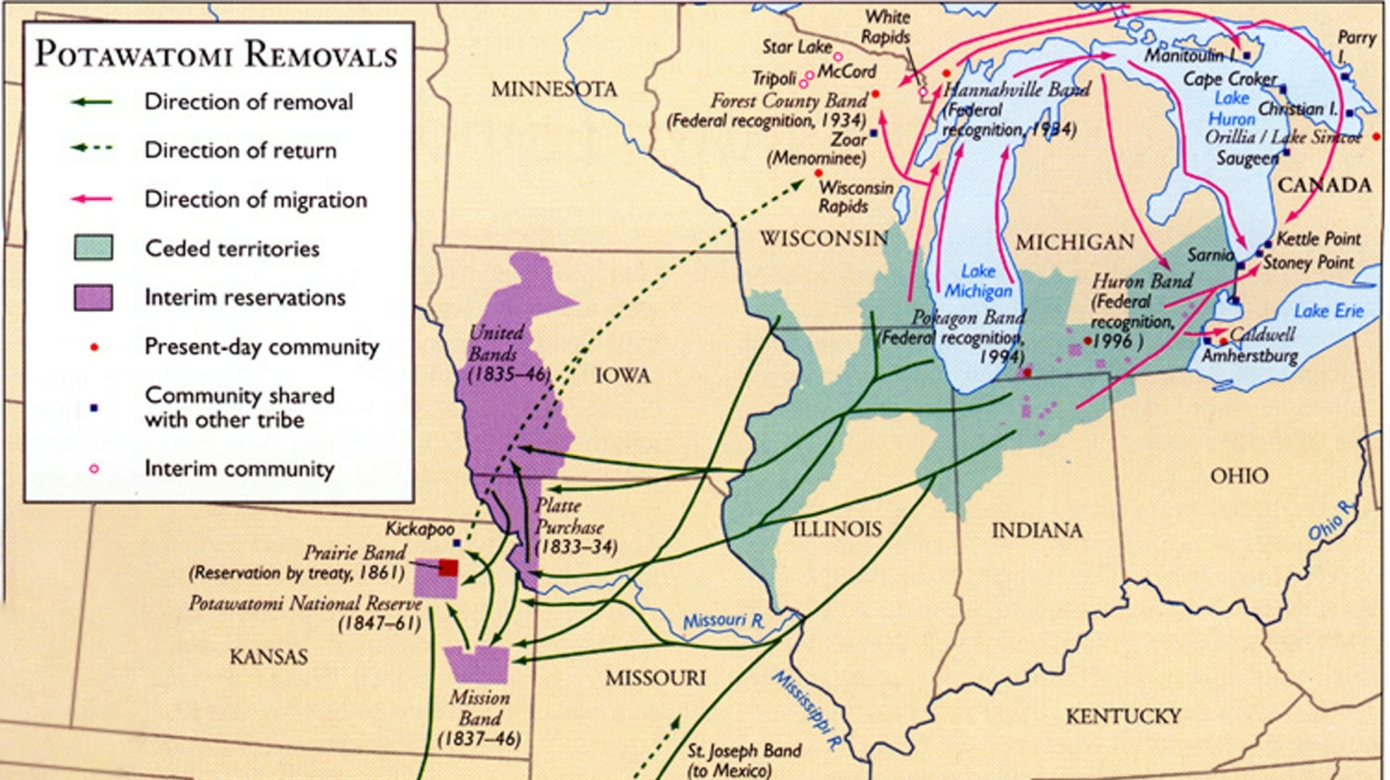

The Platte Country — also known as the Platte Purchase — was a swath of land along the Missouri River in present-day northwest Missouri. The federal government acquired the area from Native American tribes to remove eastern tribes to, including the Potawatomi. The original 1833 Treaty of Chicago included provisions for the Potawatomi removal to a portion of the Platte Country; however, Missouri wished to annex the area, and many across the state disagreed with the Potawatomi occupation. Two Missouri senators worked to amend the treaty’s language, but many Tribal members disapproved of the updates, citing their desire to continue with the original negotiations agreed upon. The Tribe’s words fell on deaf ears, and the debate pushed back the treaty’s ratification until 1835.

Despite congressional approval, most Potawatomi ignored the new language and moved to the Platte Purchase in 1835 and 1836. The Potawatomi inhabiting these lands enraged non-Native Missourians.

According to The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire by R. David Edmunds, “Many settlers believed that the region soon would be annexed to Missouri, and they crossed over into the area, clearing land and erecting cabins. During February, 1836, troops from Fort Leavenworth forced the settlers back into Missouri, but the military actions angered state officials, and Senators Benton and Linn and Congressman Albert G. Harrison redoubled their efforts to have the Platte Country annexed to their state.”

The region’s importance to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also proved problematic. Mormon founder, Prophet Joseph Smith, believed that the area that is now northwest Missouri is the Garden of Eden and the location of Jesus’ return in the second coming. This inspired church followers to establish communities.

The federal government granted the Tribe an opportunity to live in the Platte Purchase temporarily, but as Potawatomi started to move into the area, tensions between the Mormons and non-Mormons mounted.

1838 Mormon War

In 1836, Missouri leaders devised a plan to establish Caldwell County for the LDS church followers. However, the religion quickly spread. The Governor of Missouri Lilburn Boggs issued Missouri Executive Order 44 on Oct. 27, 1838, which required all Mormons to leave the state.

“The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace — their outrages are beyond all description,” Gov. Boggs wrote.

Three days later, a militia of more than 200 massacred 18 Mormon men and boys at Haun’s Mill. The state never prosecuted the mob’s actions. Shortly after, 15,000 church members left Missouri, suffering from starvation and lack of resources along the way. Gov. Boggs’ “Extermination Order” was not repealed until June 25, 1976.

Iowa

Around the same time, in an attempt to get the Potawatomi out of Missouri, General Edmund P. Gaines offered the Tribe transportation via steamboats and food to travel to Council Bluffs, Iowa.

Once the Potawatomi arrived in Iowa, they did not believe Council Bluffs held much permanency. Members leaned on their trading experience rather than farming or raising livestock to make a living, establishing commerce opportunities that helped drive economic development in the region.

“They were quick to adapt it to a wide range of opportunities that awaited them on the eastern fringe of the plains. They immediately benefitted from at least two other facets of the broad sweep of western migration: the Mormon trek to Utah, and the gold strikes in California and Colorado,” R. David Edmunds wrote in an article titled, Indians as Pioneers: Potawatomis on the Frontier.

In the mid-1840s, Potawatomi used their annuities to barter and trade with LDS church members.

“They willingly permitted the Mormons to graze their livestock (for a price) on tribal pastures and sold wood from Potawatomi woodlots for the Mormon campfires. Tribal leaders such as Billy Caldwell and Joseph Lafromboise constructed gristmills and sawmills to provide meal and lumber for Mormon travelers,” Edmunds wrote.

Spirituality

While the Mormons provided economic opportunity, their Godly connection interested many Tribal leaders as the Potawatomi looked for answers for the federal government and settlers’ negative treatment. Hearing the church’s belief regarding Joseph Smith’s divine connection, Chief Apaquachawba pleaded with Smith to speak to the Great Spirit on their behalf. Smith instructed the Potawatomi to abandon any violence with others and to read the Book of Mormon for instructions on how to solve all their current and future problems.

By 1846, the Mormon and Potawatomi relationship worried governmental officials. They feared an uprising against the United States.

According to Lawrence Coates’ article Refugees Meet: The Mormons and Indians in Iowa, “Assessing the loyalty of the Potawatomi, Governor Chambers added that they should be watched closely since they had sided with the British in the War of 1812 and were among the most savage and irreconcilable of any hostile tribe.”

Indian agents required the church members to leave the reservation. At the same time, non-Natives continued to encroach into Iowa, desiring the Potawatomi reservation for settlement.

“At each location, whites wanted land that had been reserved for these Indians. … Many Indians refused to move, and the government responded by cutting off their annuities to force them to evacuate these areas,” Coates wrote.

Potawatomi missionary

The Mormons continued traveling west until they came to the Salt Lake Valley, facing many obstacles along the way. One Potawatomi in particular, Anthony F. Navarre, followed LDS leader Brigham Young to present-day Utah where he lived among church members.

While Navarre studied Mormonism, the Potawatomi in Council Bluffs and the Potawatomi in Kansas signed a treaty in 1846. This established a single reservation in Kansas for all the Potawatomi west of the Mississippi to occupy. However, it created another set of problems, as the two groups of Potawatomi had never lived among each other and had varying stances on government affairs and more.

Navarre returned to his kinsmen in Kansas as a Mormon missionary in 1857 and quickly gained respect. He became very vocal against the impending treaty, and in 1860, hired a lawyer named Lewis Thomas to help avoid allotments and bring the Tribe together. While he did not obtain the desired results, Navarre’s actions set a precedent.

Eventually, the Potawatomi signed the Treaty of 1861, officially separating them once more. One faction, the Citizen Potawatomi, accepted land allotments based on tribal standing and the chance to become U.S. citizens, and the other, the Prairie Band, opted to remain living communally.

Although the Tribe was no longer a single group, Navarre continued efforts to represent the best interests of all the Potawatomi west of the Mississippi, which some attest his religion impacted his leadership style and tenacity.

The church’s headquarters remains today in Salt Lake City, Utah, and the Mormon and Potawatomi relationship lives on with Potawatomi Plums planted by LDS church settlers growing wild across the state more than 150 years later.

Learn more about this era in Potawatomi history by visiting the Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage center in person or online at potawatomiheritage.com.