On Sept. 30, 1809, Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami and Eel River tribal leaders signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne, which included ceding approximately 3 million acres of land in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and Michigan for 2 cents per acre.

Some tribal leaders saw the treaty as an opportunity to provide for their people while others believed it merely supported non-Native expansion in the Great Lakes region. The agreement ultimately brought an end to peace between the Unites States and many Native Nations, creating a divide that contributed to the start of the War of 1812.

Persuasion

Eager to build upon the legacies of past administrations, President James Madison worked to acquire more Native American land throughout his presidential tenure. Madison’s secretary of war, William Eustis, ordered then-Indiana Territory Governor William Henry Harrison to assemble all the Indiana tribes at Fort Wayne in September of 1809 to reach an agreement that would open lands for settlement south of the Wabash River.

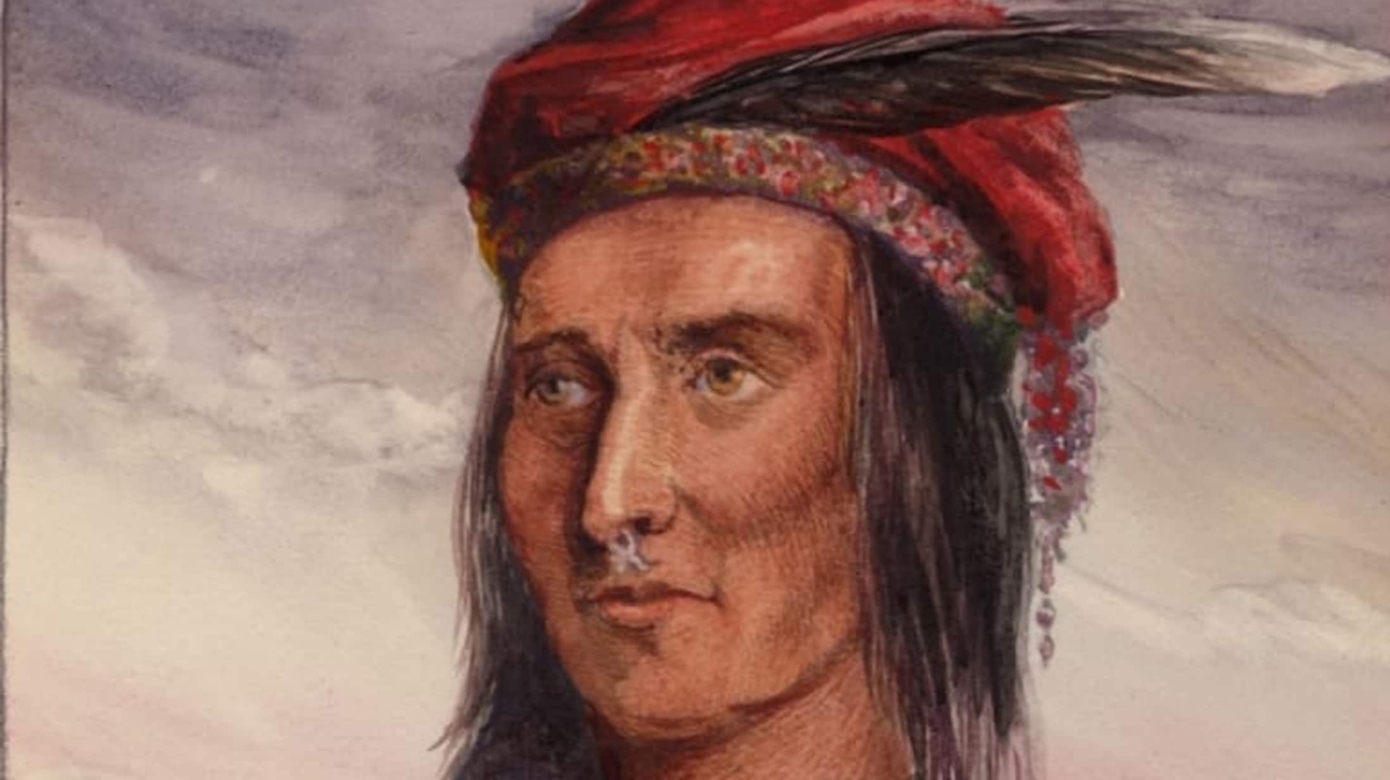

The Potawatomi “were led by Winamac, perennial friend of the United States, who earlier had assured Harrison that all the tribes would be willing to cede the lands. Notably absent were such other friendly chiefs as Five Medals and Keesass, who feared retaliation by their younger warriors if they agreed to a land cession,” wrote R. David Edmunds in his book The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire.

However, the Miami were not supportive and refused to relinquish their land claims until Winamac and several Delaware leaders convinced them otherwise.

“The Potawatomis and Delawares agreed to participate in the cession only as ‘allies’ of the Miamis and not as owners of the lands, but the technicalities made little different to Winamac,” Edmunds wrote.

In return for Winamac’s efforts, the Potawatomi received an increased amount of trade goods, which many needed to overcome the recent harsh winters. Yet, the additional provisions failed to gain the approval of all Potawatomi. Instead, Winamac’s actions at Fort Wayne caused disharmony, and younger leaders became increasingly upset with his, and other chiefs’, pro-American stance.

After signing the Treaty of Fort Wayne, Winamac continued serving as a United States ally, and fellow Potawatomi leaders Keesass and Five Medals also maintained friendly relationships with the federal government due to their villages’ locations near American military outposts.

Nativism

During this time, the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh’s movement was gaining traction across Indian Country, which Winamac and other older chiefs resented. They encouraged Native Americans to band together against white encroachment and reject the United States’ authority. Winamac’s pro-American stance fueled many young warriors to flock to Prophestown, Indiana, and follow the Shawnee brothers.

According to The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire, “Estimates of the number of Indians at Prophetstown varied greatly, from 650 to nearly 3,000, but by all accounts they posed a formidable force capable of inundating white settlement in southern Indiana.”

Winamac served as a double-agent, trying to maintain a positive reputation among his people while also providing Harrison and the federal government intelligence regarding the growing Nativist movement.

“Harrison rewarded Winamac well, but many Potawatomis disliked the chief, envisioning him as little more than a puppet for the Americans,” Edmunds wrote.

Tecumseh determined a compromise between Natives and non-Natives was impossible after he attended a failed conference at Vincennes, Indiana, with the U.S. officials and Winamac in 1810. The Shawnee chief focused the rest of the year recruiting Native warriors across the Great Lakes region to support his confederacy.

In the fall of 1811, Harrison led more than 1,000 men to confront those at Prophetstown, resulting in the Battle of Tippecanoe. The conflict created further divide between the United States and Native Americans, encouraging Tecumseh’s confederacy to ally with Britain.

The Treaty of Fort Wayne not only resulted in over 3 million acres of Native lands opening to non-Native settlement, but it also increased U.S. and Native American tensions, laying the groundwork for the War of 1812. Turmoil over land rights ensued, and less than three decades after signing the treaty, the government forcibly removed most of the tribes involved to lands west of the Mississippi.

Learn more about this era in Potawatomi history by touring the Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Cultural Heritage Center gallery Treaties: Words & Leaders That Shaped Our Nation in-person or online at potawatomiheritage.com.