As the regular major league baseball season comes to a close this month, it marks a new beginning for Cleveland’s team, officially enacting the franchise’s name change from the Cleveland Indians to the Cleveland Guardians.

The shift — announced on July 23, 2021 — reflects the franchise’s dedication to examining the sport’s racist foundations and provides an opportunity to move forward united.

“We are excited to usher in the next era of professional baseball in Cleveland as the Cleveland Guardians,” said team owner Paul Dolan.

U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland posted on Twitter, “I am glad to see that the Cleveland baseball team is finally changing its name. The long practice of using Native American mascots and imagery in sports team has been harmful to Indigenous communities.”

Since the team began, its lineup has featured numerous Native American players, including Citizen Potawatomi tribal member Isaac “Ike” Kahdot.

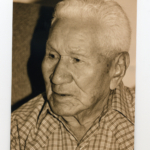

Ike

Like many other Native American professional baseball players during the early to mid-1900s, Kahdot received the nickname “Chief.”

According to a Tulsa World article published in September 1993, “A Potawatomi Indian himself, ‘Chief’ Kahdot’s only mark on the major leagues may have been but a line in four box scores. But his journey, from a small community before statehood through the major and minor leagues, touched a part of the game, and America, that has long been forgotten except in history books.”

He made his first field appearance with Cleveland on Sept. 5, 1922, against the St. Louis Browns, and in 1993, was the oldest living Cleveland player at the age of 91 until his passing in 1999.

Ike, born Issac Leonard Kahdot on Oct. 22, 1901, was the eldest of five. The Kahdots lived in a mostly Native American community known as Georgetown, near present-day Konawa, Oklahoma. He attended Sacred Heart until he was 6 years old.

“I didn’t like the priests, so I ran off every chance I got,” he told the Hownikan in 1992.

He was wrongfully blamed for smoking tobacco and received whips from the priest. Afterward, he ran away for the last time. He then attended the Friends Mission School near present-day CPN Tribal headquarters until he was 13 before transferring to Haskell Institute in Kansas.

According to a Hownikan article Baseball was good to Indian boy from Sacred Heart published in 1992, Kahdot and fellow Haskell student Luther Snake spent two days walking and hopping trains back home.

“We got lonesome for Shawnee,” Kahdot said.

Shortly after, he returned to Kansas where he began to further develop his baseball talents.

He told the Tulsa World in 1993, “My dad give me a bat, and a ball and a glove when I was growing up. And I always had that with me. We had an Injun team when I was a young kid, and my dad wanted me to play ball on it.”

As his skills grew, so did his reputation.

“By the time he finished high school … the Bartlesville Empires, a semi-pro team formed by Empire Oil and Gas Co., asked him to join their club,” according to the Tulsa World.

Kahdot averaged approximately three games per week for the Empires during the 1919 and 1920 seasons.

“They just paid me a salary, oh about $150 a month. And, well, I didn’t work. I’d go down to the ballpark and stayed down there all day,” he told the Tulsa World.

Jimmy Hamilton, minor league team manager from Joplin, Missouri, noticed Kahdot’s talents and asked him to join their spring training. He was eventually sent to Pittsburg, Kansas, in 1921 where he batted .322. Coffeyville signed him, and he became the Southwestern League’s leading runner during the 1922 season before Cleveland transferred him and two other Coffeyville players.

The Tulsa World article continued, “Cleveland had an outstanding lineup that season, including three future Hall of Famers. … Yet the Indians were 13 games out of first place at the beginning of September, which gave the club a premium opportunity to try out some new talent.”

In his first game with Cleveland against the St. Louis Browns, Kahdot was a pinch-runner in the sixth inning. He received more field time as the third baseman during his second game. Cleveland played Washington a week later before completing the regular season with games against Philadelphia, Boston, New York and Detroit.

Kahdot’s final major league appearance was versus the Boston Red Sox on Sept. 21. While his time with Cleveland was less than a month, he had the chance to meet Babe Ruth and other famous players.

He made his way back to Kansas that fall, taking a single signed baseball with him as a memento.

According to the Tulsa World, “Cleveland asked Kahdot to move to Grand Rapids, Mich., a team in which the Indians commonly sent promising players. By that time, Kahdot had set his roots in Kansas. He had a new wife, and a possible major league career didn’t seem worth the move.”

Kahdot paid the franchise $2,500 to leave his contract.

“That was some money in those days,” he told the Tulsa World.

Although he never returned to Cleveland, he continued his career, playing in the minor leagues until 1935 for teams in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and North Carolina. He then worked in the oil field before accepting a position at Tinker Air Force Base in Midwest City, Oklahoma, where he eventually retired. Over the years, the signatures on Kahdot’s baseball faded, but the memories of his time on the field did not.

Kahdot told the Hownikan in 1992 that Cleveland and baseball as a whole were good to him. Although he walked on in 1999, his legacy continues today with numerous Potawatomi building success through “America’s favorite pastime.”

Read the 1992 Hownikan article at cpn.news/Ike and learn more about Cleveland, including the name change, at mlb.com/indians.