February 2022 is the 155th anniversary of the Treaty of 1867, the last of several treaties that the Citizen Potawatomi signed with the U.S. federal government. This treaty was the final push for the first Citizen Potawatomi families to move from Kansas to Indian Territory. The U.S. Government officially ended treaty negotiations with Native American tribes in 1871.

Conditions were tumultuous in Kansas in the 1860s. Lying at the geographic center of the U.S., people began flooding west in the late 1840s during the California Gold Rush, which built up the California and Oregon Trails across the Kansas River. Residents experienced violent confrontations in the 1850s such as Bleeding Kansas that propelled the country towards the Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865.

Before 1867

In 1861, the Potawatomi signed a treaty that effectively split up those already living in Kansas. One group continued to live on a communal portion of land and later became the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Approximately two-thirds signed the Treaty of 1861 and opted for allotments in Kansas and U.S. citizenship. Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Director Dr. Kelli Mosteller said those who took allotments and started the foundation for CPN anticipated a shift toward individual land ownership as the official “Indian Policy” of the federal government. The railroads, oil companies and the federal government all wanted the land promised to the Potawatomi in 1861, as well as settlers and squatters.

“One of the great complaints about when we took our allotments on the Kansas reservation was that we were taking the best plots of land by the river with the greatest timber,” Dr. Mosteller said. “And of course, all of the quote/unquote surplus land was supposed to be going to the railroads. And so the railroads desperately wanted the timber. And they were getting very upset that we were choosing these best parcels. And as you just sit here and think, ‘Well, of course we did.’”

While some Potawatomi had found fortune and business opportunities from those stopping as they headed west, overall, conditions wore on Citizen Potawatomi in unforgiving ways. The federal government broke promises of the Treaty of 1861, not providing seed or equipment to farm the land and collecting taxes on the allotments almost immediately. It took advantage of the resulting poverty and land loss by implementing what Dr. Mosteller called an “escape clause” of the 1861 treaty.

“It was written in, and it was worded in a way, basically saying if any parties in this arrangement find that they are not thriving and doing well in Kansas, they have the option to engage in yet another treaty with the federal government to create a reservation somewhere outside of Kansas,” she said.

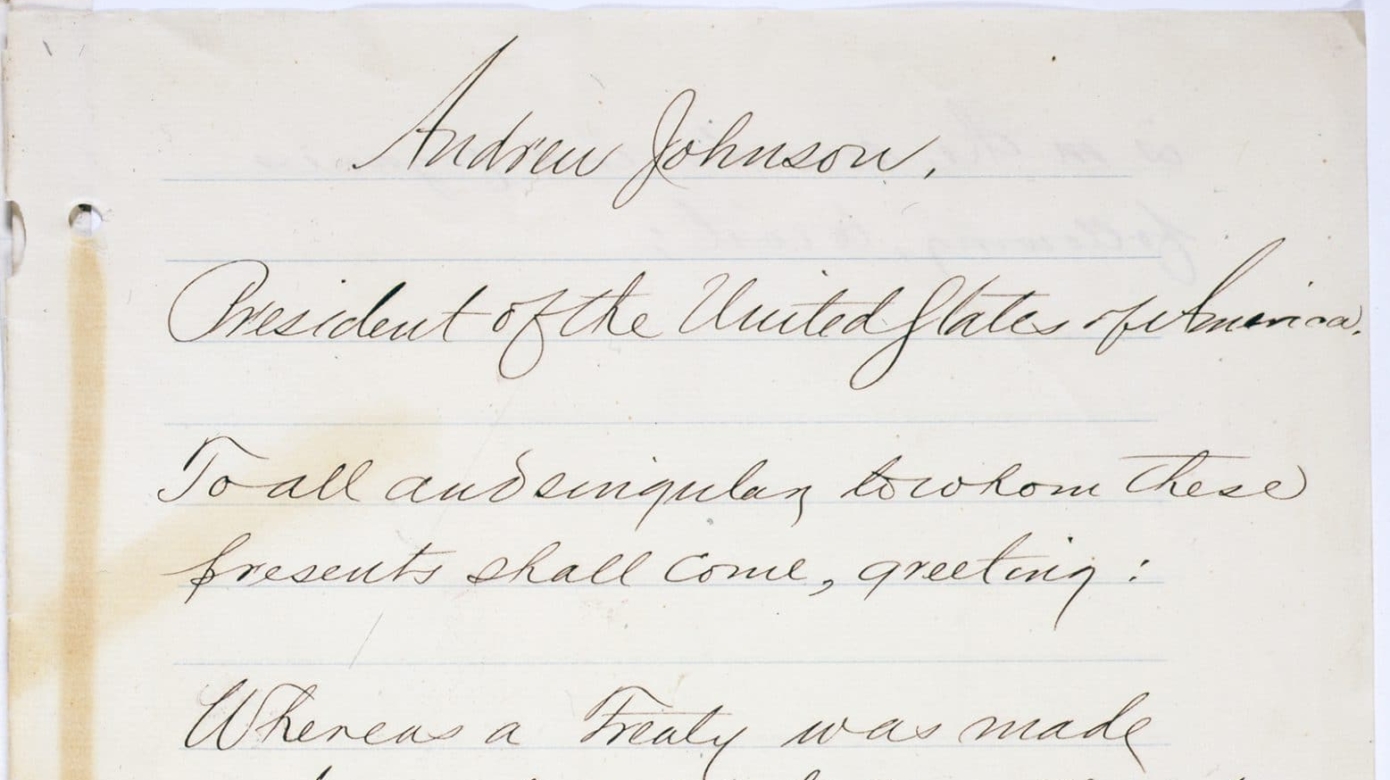

The last treaty

The resulting Treaty of 1867 outlined the Citizen Potawatomi’s move to Indian Territory and promised more than 575,000 acres, stretching from the north fork of the Canadian River to the south fork, which encompasses what is now Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma. However, the families moving had to fund the journey on their own, and it took five years for them to begin to move.

“They had to settle their business in Kansas, and traveling in groups was safer. They also had to wait for the right time of year because there was not a road really. There was a trail that they followed. There are a lot of logistics that go into that kind of move. They had to make sure that they arrived at a certain time of the year so that their wagons didn’t get stuck, so that they weren’t coming right at the beginning of winter and when they would not have time to build any kind of lodging,” Dr. Mosteller said.

The Anderson, Bourbonnais, Melot, Clardy, Pettifer, Bergeron and Toupin families were some of the first to arrive in Indian Territory with 14 wagons filled with supplies — only 28 people. They mostly stuck together, at least during the first few months after moving, knowing survival came with strength in numbers.

Dr. Mosteller called the Treaty of 1867 “one of convenience” for the federal government because it ultimately gave them access to profitable resources and land in Kansas. The pressures of assimilation and acculturation, including through legal formalities, forced the Potawatomi to relinquish their rights to land granted via treaty with the U.S. several times.

“They were signing these treaties because they knew what it meant to resist,” she said. “They knew ultimately the federal government had the power to force you to bend to their will. So we’re going to move into this new era, agree to these new terms, but we’re going to try to do so as much as possible on our own terms. We’re going to try to do the best we can to make this government work with us and for us, not just bend us to their will.”

Although the Citizen Potawatomi and federal government signed no more treaties after 1867, those same pressures continued in old and new ways. Promises continued to be broken. They found the government had sold them lands that the Absentee Shawnee had inhabited for four decades, and the Oklahoma Land Runs began less than 20 years later. Dr. Mosteller often reminds Tribal members of the Citizen Potawatomi’s resilience.

“When people ask us about cultural loss today, this is where I point out that we should be thankful for what our ancestors were able to hold onto. The language, the ceremonies, all of these teachings, they held onto these teachings and values against very great pressures that you and I today do not fully understand,” she said.

The CHC works tirelessly to preserve and share the culture of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and its history. Learn more at the Cultural Heritage Center’s website at potawatomiheritage.com. Follow the CHC on Facebook at @cpnculturalheritage.